Courtesy PID

P.M. Khan’s statements on Muslim division over Kashmir suggest a growing rift between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia

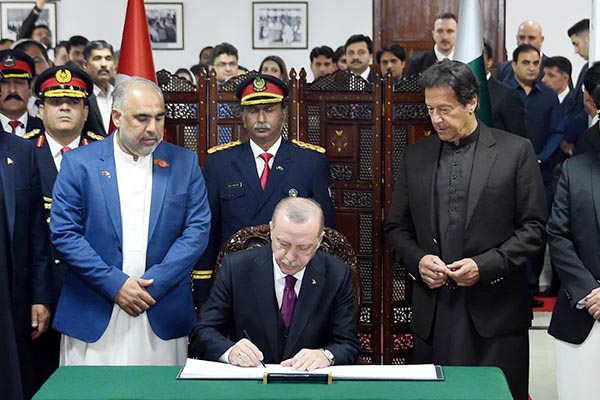

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan addressed a joint sitting of Parliament in Islamabad on Feb. 14, 2020. Prime Minister Imran Khan had said earlier said that President Erdogan’s visit to Pakistan “will strengthen ties between the two countries.” He also pointed to a foreign policy crisis when he lauded Erdogan’s statement against India on the Kashmir issue and said that “governments of the two countries were developing strong contacts with each other.”

In December last year, Prime Minister Khan had accepted the invitation to an Islamic “summit” by Malaysia despite its disputed status as a “divider” of the Islamic world between Turkey and Saudi Arabia. Under pressure, and on the advice of the Foreign Office, he ended up not going to Kuala Lumpur. There was criticism on his decision to not go, especially his “dash” to Saudi Arabia before ducking the summit, which signaled a Saudi veto on Pakistan’s foreign policy options. The comment in the media was: “Islamabad buckled under Riyadh’s pressure and failed to stand with Malaysia and Turkey, the two countries that have helped Pakistan on critical issues such as Financial Action Task Force (FATF) squeeze as well as Kashmir.”

It was said that “relations between Pakistan and Turkey became strained when P.M. Imran cancelled his trip to Kuala Lumpur at the last minute. A summit of leading Muslim countries were supposed to gather at the summit to discuss issues being faced by the Muslim community.” Why did Khan bend to a “group of Muslim countries led by Saudi Arabia who objected to the summit held outside the aegis of the 57-member Organization for Islamic Cooperation (OIC) based in Jeddah”? Erdogan added to the developing quarrel, saying Saudi Arabia had threatened Pakistan with “economic consequences” if Khan went to Kuala Lumpur.

After skipping Kuala Lumpur, Pakistan tested Saudi Arabia, asking it to convene the OIC summit on what India had done in Kashmir after abrogating Article 372 of the Constitution; the answer was in the negative. The Turkish press laid it on by sarcastically pointing to Pakistan’s dependence on Saudi Arabia “through 4 million Pakistanis” who worked there: “Saudis threaten saying that they would send Pakistanis back and re-employ Bangladeshis instead.”

In response, Prime Minister Khan visited Malaysia in January 2020 and said while being received in Kuala Lumpur: “The reason is that we have no voice and there is a total division amongst [us]. We can’t even come together as a whole on the OIC meeting on Kashmir.” Clearly, an “Islamic” cleavage was the point he was making.

Pakistan is thus being forced to join one side of the divided Islamic world and seems to have decided on the basis of its “national priority” of Kashmir to say a possible goodbye to the side that it has supported in the past. Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. had backed the military takeover in Egypt in 2013 to oust a Muslim Brotherhood government that Saudi Arabia feared but which was supported by Qatar and Turkey. In Libya again, the two sides are opposed to each other in the civil war being fought there.

Will Turkey and Malaysia “compensate” Pakistan if Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. send their expat Pakistanis back? The two have remained key contributors to Pakistan’s remittance inflows, as for fiscal year 2018-19 (FY19), collectively sending 53.7 percent or $11.74 billion.

The “split” with Turkey came into the open in the month of February 2020, when Saudi Arabia, the U.A.E. and Egypt collectively banned Turkish TV drama from their networks. Pakistan is counted among the group of countries that watch Turkish drama. Turkey sells 135,000 drama hours to 75 countries generating approximately $1 billion. What did the three Arab states say when they banned the Turkish plays?

In Egypt, the official fatwa organ of the country, the “High Fatwa Council” (Darul Iftah), published a statement accusing Turkey of trying to create an “area of influence” for itself in the Middle East via its soft power. Citing globally-popular dramas such as Resurrection and Valley of the Wolves, it went on to say that Turkish series “should not be watched in any way whatsoever.” The statement also “objected” to President Erdogan and alleged that he wanted to revive “the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East and regain sovereignty over Arab countries which were previously under Ottoman rule.”

It is going to be difficult to stop entertainment-starved Arabs from watching Turkey’s still-Westernized TV drama. In Pakistan they are watched keenly because the characters in them wear Western clothes, including girls in mini-skirts that a canny Erdogan has not banned although his anti-Kemalist, somewhat anti-women, political drive keeps returning him to power because of the rising middle class rightwing vote.

Pakistan’s romance with Turkey began in early 20th century against Kemalism in favor of the clerically led Khilafat Movement, which was stolen by Gandhi in India while Jinnah keenly read Mustafa Kemal’s biography sitting in London where he practiced law. Pakistan remained close to Turkey in the days when the two countries were part of the America alliance called the Baghdad Pact against the Soviet Union; and it must be admitted that this relationship was more sincere than Pakistani people’s feelings for the Arabs. But Pakistan has to consider Turkey’s—and Malaysia’s—ability to absorb four million expat Pakistani workers of “poor manpower” quality and offset the “loss” to Pakistan of a billion dollars if Pakistan accepts a split Islamic world because of its preoccupation with Kashmir and India.