Aamir Qureshi—AFP

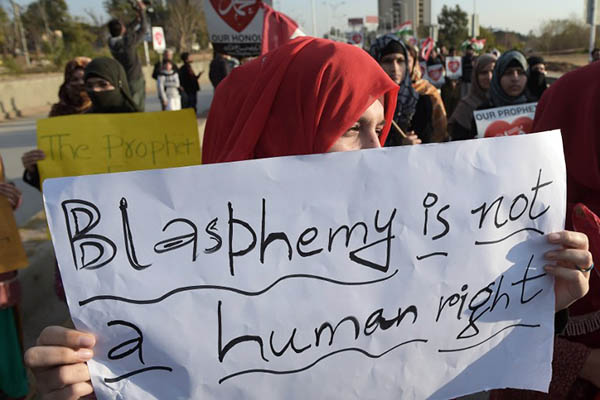

Ten years since a Danish newspaper published cartoons of Islam’s Prophet, debate on freedom of expression rages on.

Ten years after a Danish newspaper published blasphemous cartoons of Islam’s Prophet, the shockwaves are still reverberating—but experts are divided over how attitudes to freedom of expression have changed.

The 12 caricatures, published by the Jyllands-Posten daily on Sept. 30, 2005, included various blasphemous portrayals of the Prophet. The images sparked deadly protests in the Muslim world as angry demonstrators burned Danish flags and torched diplomatic offices. Boycotts of Danish products led to a plunge in exports.

Foiled terror plots against Jyllands-Posten, as well as this year’s gun attack against French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, which reprinted the Danish cartoons in 2006, have changed the conversation on Islam and immigration in many European newsrooms. But the exact nature of that change is still being debated.

“At many media outlets it has created a fear of dealing with Muslim perceptions of taboos,” said Anders Jerichow, a foreign affairs columnist at Danish daily Politiken. “And I think that is unfortunate both for the Muslim world and for the rest of the world.”

In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attack, publications in Russia, China and Malaysia—all of which have been criticized for suppressing free speech—said the magazine was wrong to lampoon Islam. But some western journalists, particularly in the U.S. and Britain, have also proved uncomfortable with the idea that anything can be done in the name of freedom of expression.

Since the original publication a decade ago, “attitudes to freedom of expression have become more polarized,” said Angela Phillips, a journalism professor at the University of London’s Goldsmiths College. The cartoon crisis “made some journalists more thoughtful about how they represent minority groups,” she said.

“In other instances I think it made quite a lot of journalists if anything less sensitive to these issues. There is in some countries an even faster recourse to a rather essentialist notion of freedom of expression,” she added.

The depiction of prophets is strictly forbidden in Islam. In the Middle East many Sunni Muslim scholars still advocate a zero-tolerance approach to depicting the Prophet, but there have been some calls for pragmatic responses.

Egypt’s Al-Azhar institution, a leading center of Sunni Islamic learning, in January condemned the Charlie Hebdo cartoons but called on Muslims to ignore them. “The stature of the Prophet of mercy and humanitarianism is greater and more lofty than to be harmed by cartoons that are unrestrained by decency and civilized standards,” it said.

Experts said the statement did not reflect a wider change in sentiment in the region. “And that controversy is not limited to the region—the cartoons also create anger and outrage among many Muslims in the U.S. and Europe,” said Scott Stewart, analyst at the U.S. intelligence consultancy Stratfor. “Fortunately most of them do not respond to that anger with violence.”

The principal threat came from violent Islamist groups using the cartoons “to provoke grassroots jihadists to conduct violent attacks in the west,” Stewart said.

In February, Danish-born Omar El-Hussein shot dead a filmmaker outside a free speech event attended by Swedish artist Lars Vilks—who in 2007 drew a blasphemous caricature of Islam’s Prophet—hours before killing a Jewish man outside a synagogue.

Since 2005, little has changed outside Jyllands-Posten’s offices in central Copenhagen. But inside, the decision to publish the cartoons—described by staff as a “routine job” at the time—has had dramatic consequences.

Envelopes are scanned for suspicious substances, windows are made of blast-resistant glass and fire alarms that previously resulted in a cigarette break and some chitchat can now force staff to seek shelter inside one of several panic rooms.

Jyllands-Posten was the only major Danish daily that didn’t carry any illustrations from Charlie Hebdo in the wake of the Paris attacks.

Danish media are on Wednesday expected to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Jyllands-Posten cartoons, but few expect them to do so by publishing new caricatures. “That would be considered too dangerous,” Kurt Westergaard, who drew an infamous image of the Prophet and who now lives under police protection, told AFP.

Flemming Rose, Jyllands-Posten’s former cultural editor who commissioned the cartoons, recently described his decision to publish them as “naïve.” It was acceptable for editors to choose not to reprint them as long as they were honest about their reasons for doing so, he said.

“You shouldn’t point fingers because people are afraid. But you have the right to point fingers if people are not honest about their fears and try to explain it away,” he told the Politiken newspaper.