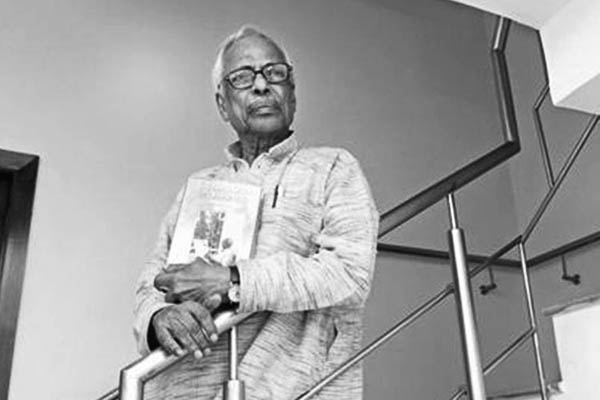

Peace activist and leftist B.M. Kutty dies in Karachi, aged 89

Veteran peace activist Biyyathil Mohyuddin Kutty (1930-2019), better known as B.M. Kutty, passed away in Karachi on Aug. 25, 2019, at the age of 89.

A Marxist, and as such no longer favored by an increasingly conservative society, Kutty lived in Balochistan where secular leaders have surprisingly exhibited greater longevity and continued to be respected. Only his middle name, Mohyuddin, proclaimed that he was a Muslim; his first- and surnames point to Kerala in India from where he had migrated to Pakistan in 1949 when he was just 19 years old.

In its profile of him, Outlook India’s article was carried under the headline, ‘A Moplah in Sindh.’ His native language was Malayali, the language of Kerala. His native city was Malabar in India’s southern state, and he came from the community of Muslims called Moplah, which textbooks in Pakistan identify as the first Muslim community targeted by Hindu sectarianism, triggering the Pakistan Movement.

It is obvious that young Kutty thought of going to Pakistan because his community looked at the country as an emerging Muslim homeland. The Khilafat Movement had triggered anti-Muslim passions, and Malabar in Kerala was not spared. Muslims reacted in the shape of what came to be called the Moplah Peasant Revolt in northern Malabar in 1921. Other violent uprisings took place too. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 killed 379 people; the Chauri Chaura (Gorakhpur) incident resulted in 23 policemen being burnt alive in 1920.

The Malabar (or Moplah) rebellion saw 2,337 rebels killed although an unofficial count put the dead at 10,000. At the time, the Moplah rebels took over and ruled for five months an area in Madras that also counted 40,000 Hindus among its population. According to an Arya Samaji count, the Moplahs killed 600 and forcibly converted another 2,500 Hindus. The Moplahs thought they were descended from Arab traders who came to Malabar in the 4th century A.D. and had been welcomed by the local rulers.

The writer of the Indian Constitution, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, was greatly shaken by the Moplah rebellion and was compelled to write the first book on Pakistan—Pakistan or The Partition of India (1945)—which the founder of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah actually arranged to be distributed among his partymen. This background accounts for Kutty’s secular, left-leaning, worldview. It attracted him to Balochistan and the indigenous movement there and caused him to embrace the more humane ideology of secularism, which finally accounted for his obscurity in “ideological” Pakistan.

That obscurity, however, did not have much impact on him. Kutty’s sojourn in Balochistan brought him the kind of solace he had long desired. During his student days in Kerala, he had gravitated to socialist-leftist views and joined the Kerala Students Federation, affiliated with the Communist Party of India. In 1946, he joined the Muslim Students Federation under the All-India Muslim League and attended the Mohammedan College in Chennai, studying science subjects for four years.

In 2011, he wrote his autobiography, Sixty Years in Self Exile: No Regrets, participating in the Left movement and influencing the province of Balochistan while serving as political secretary to the governor of the province. One can see his steady alienation from state ideology in his political roadmap: From 1950 to 1957 he was with Azad Pakistan Party in Lahore before embracing the Pakistan Awami League in Karachi. He was also deeply embedded in the politics of the National Awami Party (NAP) before it was banned in 1975. He was with the National Democratic Party till 1979 and Pakistan National Party from till 1997.

Karachi remained the hub of Sindhi-Baloch politics as Kutty got employed with the construction and engineering firm of Larsen & Toubro. It was during this time that he traveled to Lahore and met his future wife Birjis Siddiqui, an Urdu-speaker originally from India’s Uttar Pradesh. They got married in 1951 and had four children before Birjis died in 2010. His children and grandchildren survive him today.

About his journey to Pakistan Kutty wrote in his book: “Karachi stirred my imagination, so from Bombay I took the train to Jodhpur and, after an overnight stop in Munabao, we walked to Khokhrapar, Karachi. Passports had not been introduced yet. We exchanged some currency at Khokhrapar. The notes were the same Government of India notes, only ‘Government of Pakistan’ had been superimposed on top.”

Kutty unsurprisingly spent some time in Pakistani jails—connected with the “rebellion” in Balochistan—but he was not the sort to feel these incarcerations as suffering. Speaking at his book’s launch in New Delhi, he said: “Nobody pushed me out of Kerala. I went to Pakistan and became a part of its political system on my own accord. That explains the term ‘self-exile’ in the title of my autobiography. Right after that, there is the phrase ‘no regrets’. That is the truth of my life. I have no regrets for the choices I made.”

Explaining the title of his book further, Kutty said: “During my visit to Delhi in 2007, I met social activist Nirmala Deshpande and told her that I was planning on writing a memoir. She suggested the title. I thought it would reflect and summarize my entire life in just one line. She is one of the people I have dedicated my book to.”

Former Indian external affairs minister Natwar Singh, who was also present at the book launch, said, “Kutty has led an extraordinary life. He had a very difficult time in Pakistan as he was a Marxist. I have read quite a bit of the book and found it fascinating.” And Pakistan’s High Commissioner Shahid Malik said, “Your book is a fascinating account of political developments in Pakistan. Your book also took me down memory lane as it describes various developments in Lahore, which is my birthplace.”