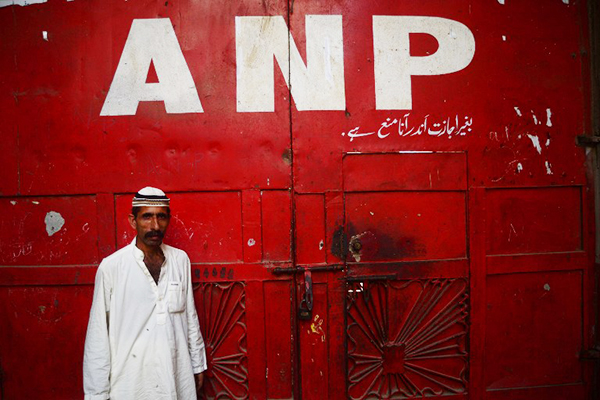

The ANP’s closed-down office in Sohrab Goth. Rizwan Tabassum—AFP

Karachi in the vice of the Taliban.

Threats from the Taliban hang over Pakistan’s historic elections, but not in some parts of the financial capital Karachi, where the militants, having chased away secular parties, hold sway.

A little over six months ago, what should have been the headquarters of the Awami National Party, a coalition partner in the outgoing government, in the working-class district of Sohrab Goth were abandoned. “A small group of Taliban came to the ANP office and told them to leave quickly. They didn’t even have to force them,” a neighbor said. ANP activists complied immediately. That was well before the start of campaigning for Saturday’s polls and they have not been seen since.

Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, an umbrella militant group which has been waging a domestic insurgency for nearly six years, has launched numerous bloody attacks across the country against what it calls the “un-Islamic” polls. It has warned citizens against voting, and through almost daily bombings and attacks it has marred the run-up to the elections, which the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, a nongovernmental organization, calls Pakistan’s most violent.

The ANP, which like the other allies of the outgoing government have been singled out for Taliban attacks, has had to close around 50 offices, some attacked in bloody strikes, in the Pakhtun-majority areas of Karachi.

In Sohrab Goth, a Taliban stronghold in Karachi, the militants have allowed others to campaign, notably religious parties such as the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (Fazl), reputedly close to the militants. “Religious parties have no problem, they can campaign. We see their supporters regularly,” said Qari Ahmadullah, a trader in Sohrab Goth’s Al Asif market.

Mullah Karim Abid, the JUIF candidate, was happy at how things were going. “Our campaign is good. In Sohrab Goth, they vote for religious parties,” he said. “Taliban? What Taliban? There are no real Taliban on the ground. All these things are fabricated by authorities.”

Haji Rahmatullah, a Taliban cadre, will not vote on Saturday but approves of Maulana Fazlur Rehman, the head of JUIF who is very hostile to the U.S. In general, Rahmatullah said: The Taliban “leadership supports anti-U.S. candidates.”

Karachi is beset by ethnic tensions between Mohajirs, the Urdu-speaking core support base of the party that controls the city, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement, and the Pakhtuns. Pakhtun districts are not a major electoral factor at this stage. Many of their inhabitants, who arrived in recent years from the northwest where they fled fighting between the Army and the Taliban, are not even registered to vote. Others are Afghans, so cannot vote. Pakhtuns are also spread out over districts, restricting their power to elect candidates from their own fast-growing community.

“Authorities have drawn red lines around Pakhtun neighborhoods,” says Abdul Latif, a preacher from Sohrab Goth. “They say they are full of criminals, and do nothing to save people from misery. The people feel rejected, and the Taliban are given a chance.”

Tens of thousands of Pakhtuns have migrated to the area in recent years, especially from the Mehsud clan of Waziristan, where the Taliban are headquartered. Their arrival has fanned deadly ethnic and political tensions in Karachi, and seen the MQM vent about Talibanization. The authorities say the Taliban commit robberies and other crimes in Karachi to fund their attacks.

“This is not an ideal situation. But government affiliates are targeted, and it helps in getting money or prisoners freed,” says Taliban cadre Rahmatullah.

But the militants’ criminal activity pales in comparison to that of the main political parties and even the police, who, according to the country’s Supreme Court, are heavily implicated in the daily crime that swamps the city. According to Karachi police, about 7,000 to 8,000 Pakistani Taliban are living in the city, compared to a few thousand in 2008-2009. They are also now better armed and able to deal with police in Pakhtun areas.

Apart from fighters themselves, the arrival of preachers from Waziristan has brought with them Islamist courts and schools. Mobile, efficient, and incorruptible, the Taliban’s courts are popular in the districts. But not all Pakhtuns are convinced. “Support among people is still limited because they still extort money from people and act like mafias,” says Latif, the preacher. “But if they control themselves and deliver to people, they can become quite popular.”