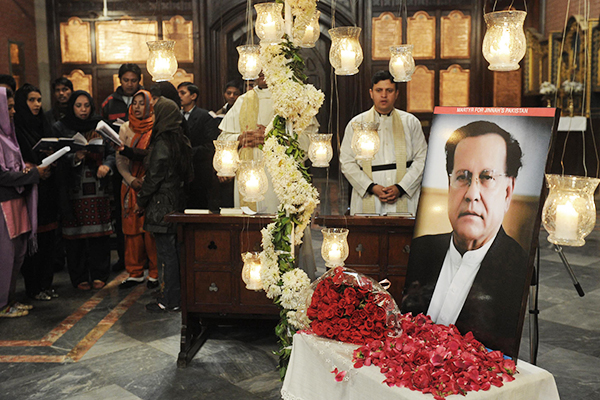

Praying for Taseer at a church in Lahore, Jan. 9, 2011. Arif Ali—AFP

How Pakistan allowed Salmaan Taseer’s martyrdom to go to waste.

The first time I saw Salmaan Taseer was at Government College, Lahore, in 1961. He walked into the classroom with Tariq Ali, and was clearly part of Pakistan’s “gilded youth,” preordained to do something out of the ordinary. Years later, I ran into him at a hotel in Nathiagali and saw him training his toddler sons to be tough and fearless.

As consulting editor of Salmaan’s newspaper Daily Times, I met him twice in 2009, at his home and at Governor House. I had to seek him out since I had never seen him at the office; and he had never tried to impose his views on the paper. I let Salmaan know that I entirely accepted his worldview and his perception of what was happening to Pakistan. I also pointed out that his son Shehryar was the most polite newspaper executive I had known, and reminded him of the “shaping” he was trying to give him at Nathiagali. He conceded that these were different times and his sons had to make their way in life more flexibly.

Based on conviction, Salmaan’s views didn’t change under pressure. As governor of the Punjab, he made Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif squirm. (One of Salmaan’s sons, ironically, carries his rival’s name; and one of Sharif’s sons is named Salman.) A governor is supposed to be a mute observer representing the president as the federal icon; but in this case the president was Asif Ali Zardari and he let Salmaan buck the chief minister, refusing to sign on when others would have kowtowed. In one case, Salmaan blocked the judicial appointments made by Lahore’s chief justice because they were based blatantly on nepotism. The top judge had written a hilariously self-damaging autobiography mostly describing his feats of gluttony and fondness for the Sharif family. Equating justice with revenge, which is what most Pakistani judges do, this judge later joined the panel of lawyers defending Salmaan’s condemned killer.

Salmaan knew what was going on. As governor, he received reports about how extremism was mushrooming out of the nonstate actors the state had employed to fight its covert cross-border wars. I have an intelligence report received by him about what was going on in South Punjab, a clear premonition of the scenario developing today as the government bends its knee to the killers it can no longer fight.

This February 2009 report on the activities of Madrassah Usman-o-Ali run by Jaish-e-Muhammad in Bahawalpur is an eye-opener. Its top cleric, Maulana Masood Azhar, is a state-supported protégé of Osama bin Laden who Islamabad tells the world it knows nothing about. The madrassah was the seat of machinations against the state, and also a mustering point for Taliban and their Arab patrons from the Waziristan agencies taking pulse of how the training of suicide-bombers was proceeding in the Punjab.

Instead of making Salmaan the emblem of our righteous objection to a bad law, we allowed the murder to go by default.

According to the report, South Punjab was under the thumb of Jaish-e-Muhammad, who had regular contacts in the tribal areas to receive instructions from the Taliban. Asmatullah Muawiya, his telltale name betraying his Sipah-e-Sahaba backdrop, trained suicide-bomber boys in Khanewal and was often found in the Waziristan region. He was, in time, made the mouthpiece of the Punjabi Taliban, now routinely issuing threats to Nawaz Sharif’s government.

More alarmingly, the report stated: “In the backdrop of the prevalent fragile security environment and fresh wave of terrorism in Punjab, comprehensive security arrangements must be made for the protection/security of the Chinese engineers carrying out drilling at Rodho Top, Tribal Area, D.G. Khan (managed by Dewan Petroleum Pvt. Ltd.) and Dhodak Oil Fields (managed by the Oil and Gas Development Company Limited).” Security of the Chinese engineers was reported as almost nonexistent at a site where Pakistan extracts its uranium. And in the “tribal area” of Dera Ghazi Khan mentioned in the report, the Taliban were also training their Punjabi cohorts. Governments have neglected these developments in their Punjabi backyard and are responsible for the way nonstate actors are assaulting the legal foundations of the state.

Salmaan knew where it was going, and decided to push back—only to find that the state and his party in power were too scared to walk in step with him.

The blasphemy law has become central to the legitimacy of the increasingly “fundamentalist” state. It is also a measure of the transfer of public loyalty from the state and the elected government to the outlaws the state has nurtured. Pakistan will have to hang “secular” Pervez Musharraf, but it can’t hang Mumtaz Qadri, the killer of Salmaan sentenced to death by the court while scores of clerics congregate in Karachi to demand that he be released and treated as a hero.

Writing in the London Review of Books in 2011, Tariq Ali, who was Salmaan’s and my classmate at Government College, observed that Salmaan did not embark on the defense of Aasia Noreen on his own; he had cleared the campaign with Zardari “much to the annoyance of the law minister, Babar Awan, a televangelist and former militant of the Jamaat-e-Islami.” Ali writes: “The 45-year-old Punjabi Christian peasant was falsely charged with blasphemy after an argument with two women who accused her of polluting their water by drinking out of the same receptacle, which provoked an angry response from religious groups. Many in his own party felt that Taseer’s initiative was mistimed, but in Pakistan the time is never right for such campaigns. [Noreen] had already spent 18 months in jail.”

Salmaan did not insult Islam’s Prophet; he committed no blasphemy. He simply protested a flawed manmade legislation that causes the victimization of disadvantaged communities in Pakistan. The role played by the rightwing media and lawyers scared off sane elements in society and the political party in power. Instead of making Salmaan the emblem of our righteous objection to a bad law, we allowed the murder to go by default. Prominent citizens, expected to uphold his cause, absented themselves from his funeral; and clerics ran away from their duty of leading the funeral. Later, as if to confirm the moral backsliding of the nation, Salmaan’s son Shahbaz was kidnapped from Lahore and is still being held for ransom.

Salmaan’s death signaled a new low point in our collective conscience. And we are reaping the tragic harvest of this depravity in the further killings of undefended non-Muslim and Muslim communities. He stood up for a poor Christian woman targeted by fanatic elements resorting to a bad law. Today, a number of helpless women of the Hindu community in Sindh are being sexually victimized without much reaction from the Muslim majority.

The Muslims themselves are punished with internecine violence for this dulling of the sense of social justice. The state releases the dogs of sectarian war from jail only to have them kill the Shia community. Salmaan wanted us to have a livable Pakistan. He was killed. Today, as we protest massacres in Quetta and Karachi with words that sound like gibberish, we are reminded of his sacrifice—which we allowed to go waste.

1 comment

He died for courageously defending the rights of the weak and oppressed. His murderer is applauded by wolves who hide themselves in Islamist garb. To bestial predators the concepts of compassion, justice, oaths of office, honour in duty are meaningless words.