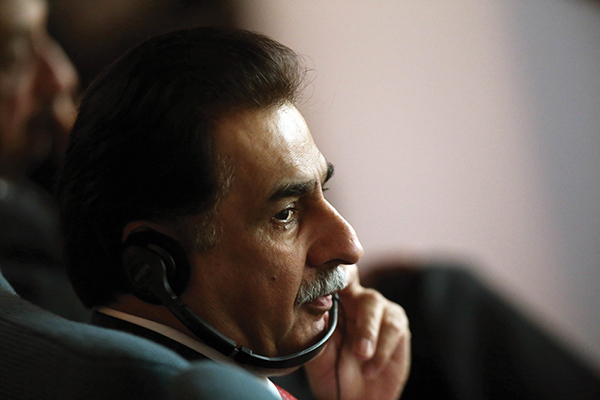

Sadiq in Kuwait, Dec. 16, 2014. Yasser al-Zayyat—AFP

It’s been a good week for Imran Khan, but will it last?

Imran Khan and his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf have been consistent in their claim that the 2013 general elections were rigged. It is this belief that led to the PTI’s months-long sit-in in Islamabad last year. But in July, a three-member judicial commission, which included Pakistan’s then-chief justice, delivered a body blow to Khan’s charges: it found no evidence of “systematic” rigging. About a month later, Khan’s claims have seemingly been given new life.

Khan had been demanding that four National Assembly constituencies be particularly examined. Three have been so far. And in all cases, election tribunals have found in favor of the PTI and against the notified winners from the ruling party, Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz).

The most recent decision came on Aug. 26 in favor of PTI’s Jahangir Tareen. But the bigger one came four days before that, against Khan’s childhood friend and former party member, Sardar Ayaz Sadiq, who was notified as the winner from Lahore’s NA-122 constituency against Khan and became speaker of the National Assembly. The tribunal ruled that voting in NA-122 had been subject to serious “irregularities” and ordered re-polling within seven days. The presiding officer, former judge Kazim Ali Malik, thus unseated Sadiq, who has said he will challenge the verdict at the Supreme Court.

But Malik’s verdict on the Khan-Sadiq fight is controversial, especially because of how it has been written.

The PMLN’s immediate and unusual reaction to it merely adds to the controversy. Information Minister Pervaiz Rashid said the former judge was “biased” and had unfairly knocked out a member of the National Assembly by associating him with irregularities actually committed by the Election Commission of Pakistan, a constitutional body that can’t be punished except by the Supreme Judicial Council. He said the verdict did not contain the word “rigging,” which would have indicted the unseated member, Sadiq.

This was followed by another salvo, from the far less restrained law minister of the Punjab, Rana Sanaullah, who implied that judge Malik was in fact avenging a refusal by the PMLN to grant an election ticket to a Malik relative for the 2013 elections. After this the floodgates opened. Malik went public with the threat that he would serve contempt notices on Rashid and Sanaullah. He also added the more damning accusation that his life had been threatened by the two. “I will not spare Pervaiz Rashid at any cost and pursue the matter legally,” he said. “I have never accepted the government’s unlawful dictations.”

Another plaint against Malik is that he has inserted in his judgment an egotistical verbal splurge about piety having no link to electoral law. The judge has begun his apostrophe—an inserted statement—with a question: whether he should do justice or follow the “doctrine of necessity,” the superior judiciary’s notorious past legal quibbling which allowed military rule.

Malik’s (edited for House style) ruling states:

“Before adopting any one of the above-said modes of trial, I have put the following questions to my own conscience: (1) Am I created simply to keep on thinking about food? (2) Am I like that animal which is tied down to a post and thinks nothing but of its fodder? (3) Am I like that uncontrolled beast which roams about and does nothing but eats its fill and does not know the purpose of life for which it is created? (4) Have I no Divine religion, no conscience and fear of Allah? (5) Am I left absolutely free in this world without any check or control, to do as I like? (6) Am I at liberty to stray, to wander away from the True Path and roam about in the wilderness of greed and avarice?”

Why this self-inquisition by someone who is supposed to safe-guard the law instead of feeling guilty about his profession or indicting the judiciary as a whole? Was this catechism a result of the pangs of guilt he felt or an advertisement of his inner musings normally kept out of court verdicts? Was this another case of self-dramatization forbidden by the written and unwritten codes of conduct of judges? A judge may occasionally get out of hand during trial, or even when delivering decisions. But such overstepping is decried by legal observers.

The judge who lets off steam knows that the public will read his dictum in the next day’s newspapers. How the judge does with the public depends on the level of insight he has achieved. If he has intellectual rigor, his outburst can be artfully restrained and be read as wisdom. But this is risky business. And Malik is no Oliver Wendell Holmes.

But what happens if a judge chooses to get personal in his judgment? He is not expected to insert his self-questionings and other pangs of conscience in his verdict. Such a judge would be considered unstable at best and dishonest at worst. A judge feeling rebellious will look bad because he is supposed to remain within the law. And what if he is a bad writer or doesn’t bother by habit to read carefully what is going public as his opinion? If the grammar is defective, and if there is needless repetition, his apostrophe will look commonplace and trite.

Malik’s aside suffers from flaws of composition which he should have taken care to remove if he is not a careless man. (Most judgments in Pakistan are carelessly written; people at times detect blunders serious enough to take away from the serenity of the text.) Malik’s reference to food is a tautology that destroys the text’s serenity. Instead he should have explored other traits of the sensual man he wanted to condemn. “Greed and avarice” could have been explored a bit further, apart from food, and if the writer was not creative enough or short of time, he should have self-censored and reprimanded himself for having stray thoughts unconnected with the work at hand.

Is there something dishonest in showing off your religiosity in public? Judges have been known to attend public meetings, in violation of their code of conduct. But Muslims consider Islam above all codes. Judges sit in etikaaf (pious withdrawal) in the last week of Ramzan, abandoning their backlogged courts for heavenly reward. One High Court judge actually addressed a public meeting to invite Muslims to kill blasphemers because he was angry at NGOs protesting against defects in the blasphemy law.

The Supreme Court may also find Malik’s pious meanderings problematic. Until then, at least, the PTI can party on.

From our Aug. 29 – Sept. 9, 2015, issue.

Editor’s Note: On Aug. 26, the PMLN announced it will go for by-elections in the constituencies where elections have been voided instead of challenging the tribunal decisions in court.

2 comments

Just wasted my few minutes

I agree entirely with this author’s sentiment, our judges here are prone not just to encroach on to the domain of other citizens serving in the legislature or executive but they even transgress too freely into the domain of Allah.

They take it upon themselves to act outside the confines of Law as self appointed arbiters of right and wrong – a role which belongs only to the Almighty Allah.