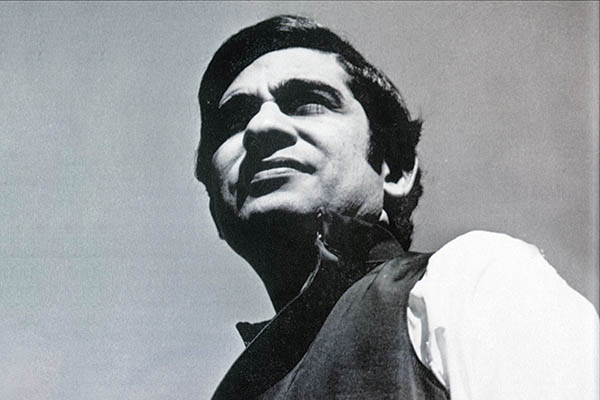

Courtesy of Musarrat Hassan

Celebrating Ijaz ul Hassan, artist and defier of dogmas.

Her sixth book, art historian Musarrat Hasan writes, is “an effort to provide a perspective and insight into the life of a man whose constant and primary bone of contention with his world and the world at large has been, and still is, his never-ending quest for improvement and change and the insatiable urge to put all things right.”

The author of Ijaz ul Hassan: Five Decades of Painting is singularly qualified to expound on the evolution of that man, on the Lahore-based artist and writer’s person, politics, and palette: they’ve been married 56 years.

The book celebrates all things Hassan in order to provide the context necessary to truly appreciate his hard-earned place in Pakistan’s art world—from his athlete days at Aitchison to his stint at London’s Saint Martin’s School of Art to Cambridge (where he completed a degree in literature) to his training by legendary artists Khalid Iqbal and Moyene Najmi to his imprisonment in the dungeons of the Lahore Fort during Gen. Zia-ul-Haq’s rule to his political career with the Pakistan Peoples Party.

“He’s been ahead of his times in terms of aesthetic sensibility, and especially the relationship of art to culture and politics,” says critic and painter Quddus Mirza. “There’s an openness and ability to reconcile seemingly contradictory views and practices that make him one of the most important people in Pakistani art.”

Hassan was awarded Pakistan’s Pride of Performance award in 1992.

In the earlier years, Hassan’s work was more figurative and aimed at forcing thought. Face to Face (oil on board, 1972) demands viewers confront the brutal horror of Pakistan’s civil war, which led to East Pakistan becoming independent Bangladesh. Hassan, 78, doesn’t believe in art that “says nothing, hears nothing, and even sees nothing.” This desire to out ugly truths led to Hassan being jailed twice. The seemingly apolitical was political, says journalist Khaled Ahmed of this period, “His rare ‘inhabited’ canvasses are a poster-like defiance of the dogmas injected into the veins of an impoverished population.”

During the 1980s, when his work was censored if not simply turned away by galleries petrified of the government, Hassan found nature to get his point across. This led to his well-known (and, for some, timeless) series of garden paintings. He showed meaning in the banal, imparting lessons through depictions of the natural world. Let a Hundred Plants Grow (oil on canvas, 1988) looks, at first glance, an unspectacular garden. The mural actually celebrated the impending return of democratic rule, explains Musarrat Hasan: “If all these plants of different species, color and temper can live in harmony, why can’t human beings rise above their sectarian, linguistic and clannish identities and embrace others of different faiths or culture?”

According to some critics, as Hassan’s involvement in politics grew and Pakistan’s many promising starts and restarts didn’t appear to pan out, his pieces seemed to become bleaker. Musarrat disagrees. “Ijaz’s love for the beautiful, the chaste, the pure, is ever present.” Far from being weighed down by despair, “He has always maintained that, amid all the filth and squalor of the world, it is important to not always depict the sad aspects of life.”

Artist Hassan is his own toughest critic; he says he remains “a mere weed aspiring to blossom one day.” Five Decades establishes, even to the uninitiated, that Hassan’s work reflects his life—evergreen and always in bloom.

From our Feb. 25 – March 11, 2017, issue.

4 comments

A comprehensive article that touches all aspects of life and works of Mian Ijaz UlHasan ‘s life and work Wish him all the honours and success and a healthy long life.

Beautifull sir gee, you deserve more then this sir

The truth Mian sb sometimes mention about art is really true. I like that.

Wonderful coverage. Congratulations to Mian sahib and the author.