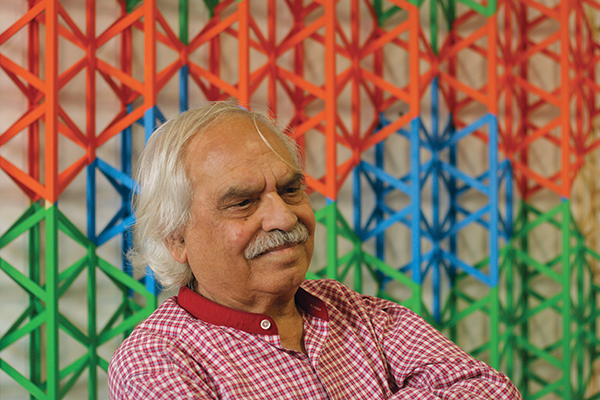

Araeen at his London studio.

Rasheed Araeen, an art-world revolutionary.

In 1965, Rasheed Araeen met Elena Bonzanigo at a café in Earl’s Court. It was the usual story: he looked at her, she looked at him, and they fell for each other. “She was interested in art, literature, classical and avant-garde music—these were the things we shared,” Araeen says of his wife. “But there was a subtext, too. At that time Omar Sharif was a very famous actor. She was very fond of him, and I looked like him. There’s always an image that’s imposed on you.”

It is a mischievous twist for a man who has made a career fighting those imposed images, the projections of Otherness, that frustrate the universality of “a humanity that is not divided by race, color or cultural differences,” as he wrote for The Third Text, the seminal postcolonial journal he founded and edited from 1987 to 2011.

That fight and the journal it spawned have made him famous. The former Black Panther is now hailed as a prophet of globalization in the international art market, and the revolutionary outsider has, up to a point, become part of the establishment, with profitable cubicles at Art Dubai and Frieze and a new solo exhibition this year in New York.

In June, The New York Times recognized Araeen, who was born in Pakistan in 1935 and moved to London in 1964, as “an art-world legend since the 1980s.” The Third Text, it said, “not only gave a voice to contemporary non-Western and nonwhite artists but also helped initiate an entire rethinking of 20th-century art history. Mr. Araeen also produced some of the most influential writing of the time … and organized shows like “The Other Story” in London, which laid the foundation for the concept that modernism, far from being a Western phenomenon, had happened all over the world, on different schedules.”

In his London studio, Araeen, 80, walks with a prop and waits at his coffee table, a glass pane atop four of the now iconic blue boxes conceived in 1966 and stacked together in 1968 as Chaar Yaar (Four Friends). Araeen developed and produced his sculptures—or “structures,” as he prefers—independent from but simultaneous with the development of New York Minimalism. Overwhelmed by an Anthony Caro exhibition in 1960s London, Araeen put away his early Karachi paintings and developed works inspired by the sculptures but rejected Caro’s sense of hierarchy. “I never liked to follow anybody,” he tells Newsweek. It is only in the last 10 years that Araeen’s work has been incorporated in the Minimalist canon. Even though, he says, he created the first Minimalist sculptures.

His own experience of an independently developed Minimalism gave birth to Araeen’s idea, increasingly common currency, that modernism is a global rather than Western movement. Araeen’s structures were distinguished from mainstream Minimalism by a supporting diagonal drawn from Araeen’s day job in the 60s as a civil engineer for British Petroleum. And while Donald Judd gloried in pristine, abstract chrome perfection, Araeen’s are hand-painted on wood and handed back to their audience.

Zero to Infinity, proposed to the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, in 1968 but not exhibited until 2004, invited visitors to arrange and rearrange Araeen’s structures; the static geometry of control becoming dynamic and infinite.

“You can’t reach infinity, you can move towards infinity. You can never reach utopia, because utopia doesn’t exist, but you can aspire for utopia, a better world,” says Araeen. “I wanted to do these projects so ordinary people can become creative. It’s a symbolic example of how one can bring individual creativity with the creativity of the people and one day break the symmetrical structure and put things together according to their own idea.”

In the studio, Araeen keenly shows a video of Zero to Infinity in action at MALI, Peru’s Museo de Arte de Lima. Disclaiming the musak (“I did not choose the music”), Araeen delights in seeing the structure in play, especially with the work transported to a local park. “Children love it.”

“I cannot transform the whole world,” he says. “But through my work I want to empower people so they can take decisions about what to do with their creativity and how to use their creativity to transform the world.”

It is a utopianism both imaginative—as with Araeen’s imperial project of Meditteranea, dissolving the barriers between religions and the First and Third Worlds—and practical: those money-spinning art-fair cubicles will fund agricultural communes in the Pakistani provinces of Balochistan and Sindh.

Araeen has always been something of a dreamer. Growing up in Karachi, the son of a government official in Balochistan, his first exposure to art was through his mother’s embroidery patterns. He later joined drawing classes at the U.S. Information Service library, but it was the life around him in Karachi which inspired his move into art and modernism.

“Other artists, particularly those interested in modernism, either tried to imitate the Europeans or they were involved in their own personality,” he says. “My own approach was to my experiences of things in Karachi—street scenes, boats, water, water towers in Hyderabad. Those things inspired me and became part of my work.”

The move to abstraction—with realist port scenes whittled down to their elements, the angles of hulls buffeting against each other to the same tides mixed with echoes of chance encounters with burning tires and children playing with hula hoops—produced an aesthetic which continued through his now most recognized period of work in London in the mid-to-late 60s.

“In the artistic world, there is the creative phase and there is the productive phase,” says Araeen. “The creative phase is very brief. In that period, you stumble on a new idea and then you constantly pursue that idea and put it into production. That’s what I’m doing here, I’m producing work.”

These days Araeen’s assistants are recreating the lost or destroyed lattice sculptures from his fecund mid-60s days for newly interested museums and collectors. Araeen’s structures are being expanded in shape to embrace the oscillations he saw among Karachi’s hula hoopers to produce pieces that thrill with the dynamism and rhythm of a port city, evoking a limitless geometry.

That sense of an underlying rhythm found its most literal expression in Chakras (1969-70), inspired by another port. In the late 60s, Araeen took a studio in a warehouse at St. Katherine’s Docks. Each day, to reach the warehouse, he crossed a small wooden footbridge. He became fascinated by the ebb and flow of the water in the dock beneath, tracked by the movement of flotsam and jetsam washed up from the Thames. Araeen has written often of the artist’s duty to undermine what he calls “narego,” the narcissistic ego of the artist at the heart of the 20th-century’s history of Western artistic genius. In Chakras, Araeen cast 16 indistinguishable discs, each two feet across and painted red, from the bridge into the docks and recorded their flow among the other detritus of London life. In the process of the work, they were destroyed. Araeen repeated Chakras in Paris before bringing the work home to Karachi in 1974.

“Other people would call it spiritual, I would call it aesthetics,” he says. “I encountered a particular environment and Chakras were a particular response to that environment.” A work that began as an observation of the ebb and flow of the tide became a critique of the deteriorating, expanding cities of London, Paris, and Karachi in the late 60s and early 70s.

As the 1970s progressed, that social critique became violently raw and took center stage.

“I was pursuing art within the context of aesthetics,” says Araeen. “In the 70s, I became aware of social problems, which I realized were an obstacle in the way of aesthetic experience. And I couldn’t carry on my work without dealing with these problems.”

Enoch Powell’s vision of a nation foaming with blood in 1968 sparked imperialist racist attitudes under pressure from mass immigration, emboldening British nationalists. At the same time, Araeen came face to face with prejudice in the art world. Despite a prize from Liverpool’s John Moore University in 1969, Araeen found it almost impossible to find exhibition space. After joining the British wing of the Black Panthers (“a mistake,” he says) Araeen confronted these attitudes in his work.

The artist’s Art Dubai 2015 exhibition.

Araeen’s first explicitly political work, For Oluwale (1971-1973), a collage of news in commemoration of the first black man to die in police custody in Britain, was exhibited in the reception of a north London library, the only space he could find. Araeen would spend much of the next 20 years out of work, largely ignored by the art establishment.

His work became riotously confrontational—from Paki Bastard (1977) to What’s It All About, Bongo? (1991), titled after racist National Front graffiti scrawled on his Golden Verses (1990). A new awareness of the limits imposed on him as a “Pakistani artist” led to collages in the 80s featuring cruciform images satirizing the Crusader myth of Western cultural supremacy. But it was Araeen’s new theoretical insight that had the greatest impact. First realized in Preliminary Notes for a Black Manifesto (1975-1976) and later in 70s journal Black Phoenix, Araeen’s critiques would mature in the 80s to become the foundation stone of The Third Text, the journal that won him global renown as a thinker.

In 2011, Araeen was removed from the editorial chair of the influential journal he founded, betrayed by a friend he had made director. The Third Text’s advisory board promptly resigned in solidarity. Still, Araeen continues to champion the journal’s success: “There were a lot of voices coming from other parts of the world that were oppositional voices,” he says. “But there was no publication that would allow those voices. We were able to present those voices that otherwise would not have been heard.”

It has been an incomplete revolution. While Araeen welcomes the new voice given to international artists in the marketplace, it has led to multicultural cages, trapping artists within their cultures of origin. Have any from the younger generation of Pakistani artists managed to escape this?

“No, they have to carry the Pakistani flag in order to interest the art market, otherwise the market won’t accept them,” says Araeen. “This is the problem I am facing now. Although my early work goes beyond being a Pakistani, there is an expectation that I should project myself as a Pakistani. This is a global problem. The Chinese have to be Chinese; the Japanese have to be Japanese… that is part of globalization. No one these days can be just artists.”

But even that acceptance is progress. When Araeen brought together international artists for his 1989 show “The Other Story,” prominent British critics derided the artists’ pidgin modernism. In his recent retrospective in Karachi, “Homecoming,” Araeen schools the West with a Modernist Islam—inspired by Golden Age Islamic thinkers Ibn Rushd and Al-Farabi—that both rebukes Western structural racism and cultural alienation and offers a brilliantly colorful riposte to the monochrome literalism of the Islamic State and the Taliban.

“I’ve been hitting my head against the thick wall of European culture for the last 50 years. And I began to think, ‘why bother?’ So I looked into Islamic history and found there was a golden age which helped Europe enlighten itself and that’s what I did in Karachi.”

It is a realization of Araeen’s vision of art in Preliminary Notes for a Black Manifesto: “We can and must stand on our feet and oppose those alien values, as well as our own, which obstruct radical change by preventing the development of the internal dynamism of our people; and in this process of confronting these values we can and shall discover new art forms that authentically reflect our own reality today.”

Those words still hold true today.

“It’s not only about my work, but about art—how it should be made now,” says Araeen. “It was my intention that it should transcend.”

From our Aug. 29 – Sept. 5, 2015, issue.