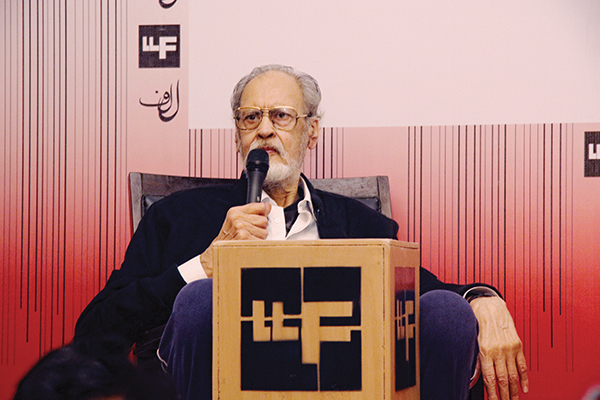

Hussein made his last public appearance at the Lahore Literary Festival in February.

Abdullah Hussein (1931-2015).

It took Abdullah Hussein a train, a donkey-cart ride, a winding walk, and several hours to get to the home of the Great War veteran he had befriended weeks earlier in 1962 at a Daud Khel hospital, where Hussein was recovering from malaria. “I am not a literate man,” the old man Hussein had come to see told him, “but there was with me in the trenches an educated soldier, no more than a boy, who wrote these lines about everything happening around us before he was killed.” The one-legged former soldier then handed over to Hussein a stack of papers with weary, anguished battlefield observations in Urdu.

Hussein, who had been working on a love story set in 1947 India, now had a first-person account of World War I. He began imagining what the young soldier’s life would have been like had he lived. Hussein rethought his Partition novel and merged the stories of the old and young soldiers to fashion the disabled Naim Beg, protagonist of Udas Naslein, first published in 1963 and the work Hussein is most famous for.

One of Pakistan’s most successful and reclusive authors, Hussein lost his seven-month battle with leukemia on July 4. He was 83. Author Asif Farrukhi says Hussein “was a major novelist who was very clear in terms of his scope, vision, and the kind of ground he covered. We don’t have a lot of authors like that.”

Born on Aug. 14, 1931, in Rawalpindi as Mohammad Khan, the author adopted a penname in 1962 because one Col. Mohammad Khan was already a published author of some renown. “He knew somebody called Tahir Abdullah Hussein,” Nur Fatima, Hussein’s daughter, tells Newsweek. “He liked the middle and last name together. It wasn’t a long drawn-out thinking process; it was a spur of the moment thing because of his publisher’s insistence.”

To introduce the upcoming novelist to Urdu-reading audiences, the publishers shopped around Hussein’s short stories, the first of which, “Nadi” (Stream), appeared in the journal Savera that year under his new moniker. The following year, Hussein’s 500-page Udas Naslein became a bestseller and won him the Adamjee Prize for Literature. Two days before the ceremony, the powerful Nawab of Kalabagh, who viewed the novel as obscene and deleterious to the Urdu language, pushed to have it banned. It didn’t work. Udas Naslein has been published in 15 languages, including Finnish and Chinese, and remains in print. Hussein translated the work into English as The Weary Generations for the 16-strong UNESCO Collection of Representative Works from Pakistan.

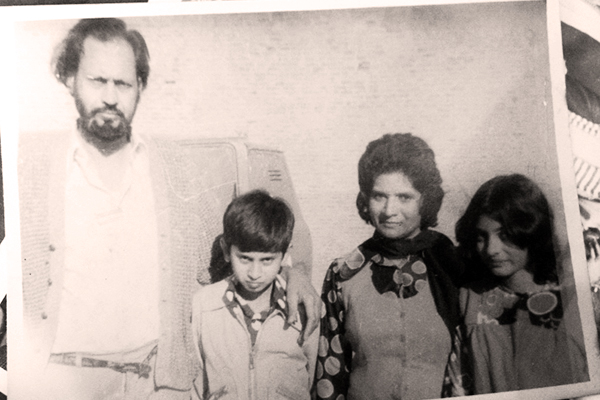

Hussein, whose mother died when he was 8-months-old, grew up with his two sisters and excise-officer father near Simla brewery. He went off to train as a chemical engineer in Canada in 1958, and returned home two years later to take up a job at the National State Cement Agency in Daud Khel. “Everybody knows he was so bored there,” says Fatima. So he took up writing. In 1966, having earned accolades and acclaim for his fiction, Hussein, with his wife and two children in tow, moved to the U.K. to work for the North Sea Oil and Gas Exploration Board.

It wasn’t until almost 15 years later that Hussein would publish his next work. Nasheb (or Downfall by Degrees), a collection of short stories inspired by his 1977 visit to Libya and published in 1981. This was followed by the set-in-Kashmir Baagh (The Tiger) in 1982—“My favorite novel and it has always been underappreciated,” said Hussein. Qaid (Captivity) was released in 1989 and Nadaar Log (The Dispossessed) in 1997. Three years after this, he published Émigré Journeys (which he translated from his short story Waapsi Ka Safar about a family of illegal migrants). Hussein’s works continued to find resonance at home and abroad: both PTV and the BBC filmed them into shows.

“His sense of exile was very strong and it runs through all his books,” says Fatima. “All of his characters are people who don’t quite fit in.” That is a place the solitude-seeking Hussein was likely familiar with. “He had no time for small-mindedness and didn’t suffer fools. He got very frustrated with Pakistan very early.”

‘I am perhaps the only man in this country who doesn’t own a cellphone.’

Farrukhi agrees. “He was a reclusive and difficult person; he didn’t have a lot of friends but he was very active on Facebook, always commenting and sharing his views.” Udas Naslein, he says, would get the towering Hussein—he was 6’4”—wound up because that first novel cast a long shadow over his subsequent works. At the same time, says Farrukhi, Hussein could light up the room with his eloquence, wit, and impatience for political correctness.

When the Pakistan Academy of Letters invited him in May to receive the Kamal-e-Fun Award, he told them to just mail him the check. Hussein didn’t do the publicity circuit. But in February, he made a rare public appearance at the Lahore Literary Festival. “You’d be surprised to know that I am perhaps the only man in this country who doesn’t own a cellphone,” he emailed LLF organizers, “I make do with a single landline on which I am always available.” Hussein was also always available on Facebook, a platform he felt at home with despite his long years.

Over the last 15 years, Hussein split his time between Lahore and Murree. It was a daily ritual for him to put his feet up, smoke his pipe and scribble away on a notepad. “He could write sitting anywhere as long as he was alone,” says Fatima. “He’d always mumble to himself as he wrote.” In all, Hussein produced eight books of which three he translated into English. His unpublished novel, The Afghan Girl, is the only work he wrote in English. It made the longlist for the 2008 Man Asian Literary Prize that considers yet-to-be-published fiction.

Fatima only discovered the Afghan manuscript and its recognition in June when she came across the Man Asian Prize certificate tucked away in a box at Hussein’s home. (This wasn’t entirely odd: the prizes Hussein picked up along the way would always end up in moth-eaten cardboard boxes.) “I asked him why he hadn’t published it and he said, ‘I finished it seven years ago but this one still needs some more tinkering.’”

Hussein kept tinkering with his story of a CIA agent who falls for an Afghan woman. When Abbottabad happened, he revised it to include Osama bin Laden’s death. He told his daughter all the changes he had in mind and how his notes on the margins were organized. “In his own way, he told me where to pick it up from and what to do with it,” she says, adding that The Afghan Girl will be published.

Years ago, Hussein’s wife asked him to attend the funeral of a distant relative. He lowered the newspaper he was reading and declared, “I don’t do funerals anymore.” How then, she said, could he expect others to come to his funeral? “Well, I’ll be dead,” he drily replied, “So that’s your problem.” In the end, it wasn’t a problem at all. Hussein’s funeral was packed—too packed, probably, for his liking.

Hussein with his wife and children, who survive him, as do six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Timeline

1931: Born in Rawalpindi on Aug. 14

1956: Hussein’s father dies; his mother died in 1932

1962: Publishes first short story, ‘Nadi’

1963: Udas Naslein is published, wins Adamjee Prize

1966: Moves to London with his family

1981: Publishes Nasheb, his first work in 15 years

1995: PTV airs a six-episode serial based on Nasheb

1996: Udayan Prasad directs Brothers in Trouble, a BBC feature film based on Waapsi Ka Safar

2000: Returns to Pakistan

2008: His unpublished novel, The Afghan Girl, is longlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize

From our Aug. 1-8, 2015, issue.