What we can glean about Ajmal Mian from his own book.

[Editor’s Note: The frontrunner for the post of National Accountability Bureau chairman is Mian Ajmal, a former chief justice of the Peshawar High Court, not Ajmal Mian, a former chief justice of Pakistan. Politicians have used Ajmal Mian and Mian Ajmal interchangeably resulting in the confusion. We regret the error. This article and its original headline, “Pakistan’s Next Accountability Czar,” have been revised accordingly.]

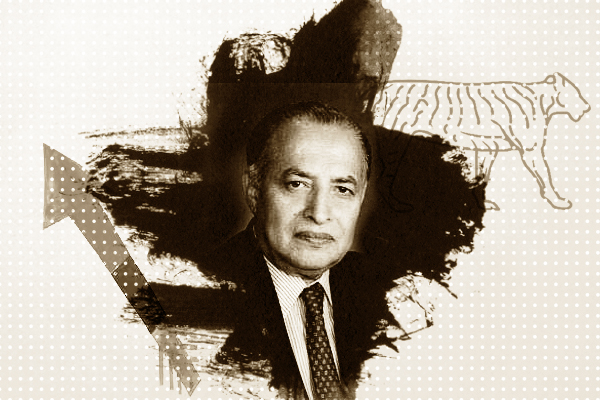

Minhaj Ahmed Rafi

Ajmal Mian became controversial when he reportedly allowed a coup within the Supreme Court against chief justice Sajjad Ali Shah in November 1997, when Nawaz Sharif was prime minister and the target of Shah’s “activism.”

Born in the shadow of Delhi’s Jama Masjid, in 1934, to a pious family doing leather trade (which was largely open only to non-Hindus), Mian’s father had wanted him to join the business which would have meant looking after his rather prosperous English Boot House in Karachi; but a fakir in Agra had prayed that Mian become a “balistar” (barrister). According to Mian’s 2004 book, A Judge Speaks Out, he had been a good-looking young man while at Lincoln’s Inn but when he returned to Pakistan, his mother found him thin. He writes that she fed him paratha and halwa until he became rather portly, groomed and, one might say, fit for the wig under which he was to sit for long years at the Sindh High Court and Supreme Court.

Back in Karachi, Mian took up as a junior at the chamber of Pakistan’s famous lawyer Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada and started appearing at the High Court while teaching, from 1958, at S.M. Law College, “to improve his speaking capacity.” Others who taught at the College included Nasir Aslam Zahid, who became his colleague at the Supreme Court in the stormy 1990s; and among those taught by him included Saeed-uz-Zaman Siddiqui, who succeeded him as the country’s chief justice, and Wajihuddin Ahmed, who became a judge there. Today, the only factor standing against Mian’s NAB appointment is his old age.

For 19 long years, Mian was the lawyer of the Karachi Port Trust and he served it well after the bureaucrats there accepted the fact of his integrity and could no longer fool around with him. In 1961 he married his wife unseen, which was okay for a young man who had gone through studies in England without touching a drink and had actually saved £500 to buy his first car on his return to Karachi.

Mian was meticulous and studious which traits were enhanced by the fact that he had found a true vocation. He was also conservative, which is what judges who act on the basis of case law are required to be; but he was not Islamist-radical like Justice Rafiq Tarar, who actually bent the knee to Maulana Manzur Chinioti just before the great apostatizer’s death at the Sharif Hospital in Lahore in 2004.

Mian writes well, interspersing his narrative with cases he thinks bear re-telling. His book is undoubtedly more elegant in language than those written earlier by our half dozen or so judges. The centerpiece of the book is the Greek tragedy of the Judges’ Case and the downfall of a Supreme Court chief justice after a revolt among the judges.

But to begin at the beginning, the 1993 case against the dissolution of Parliament by President Ghulam Ishaq Khan came up before Chief Justice Nasim Hassan Shah’s Supreme Court. In the past, the court had been accepting the dissolutions on the basis of “national interest” or “the doctrine of necessity.” This time the court decided to go by the Constitution, only to find that the chief justice was queering the pitch by succumbing to that old malady of the judicial person: excessive verbalization. The court decided to restore Sharif’s government. Good judge Justice Shafi-ur-Rehman wrote the judgment, with which everyone concurred except Justice Sajjad Ali Shah. Just as Chief Justice Shah circulated the “great judgment,” Sajjad Ali Shah, too, got his dissenting note bound and circulated. The bewigged gentlemen were doing straight politics.

Ajmal Mian relied on the Indian Supreme Court’s judgment in the Advocates on Record Case to say that “consultation” with the chief justice of Pakistan over appointments had to be binding. He also made the seniority principle binding on the government and virtually obviated the practice of keeping acting and ad hoc judges on the leash in order to get “desired results.” Sajjad Ali Shah, seeing that his own position as a superseding judge would be jeopardized, set aside the judgment written by Mian and wrote his own. Needless to say, the PPP, bitten by his “activism” despite the fact that he was “facilitated” by the PPP, went on the warpath and Sajjad Ali Shah felt the heat of it. He survived because in 1996 President Farooq Leghari dismissed the PPP government, paving the way for another calamity for the judiciary, a PML government with two thirds majority in the National Assembly. This time the Supreme Court got divided and got rid of its chief, whom Ajmal Mian succeeded.

3 comments

it ends rather abruptly.

well documented story.

Nice article…………