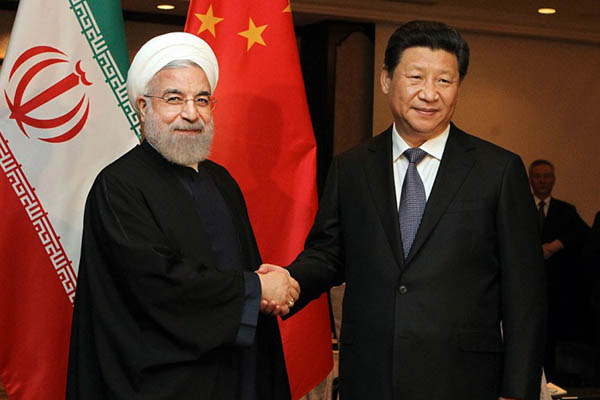

Iran President Hassan Rouhani with China President Xi Jinping.

What do Iran’s growing links with China, and distancing from India, mean for Pakistan?

Iran and China have inked a long-term agreement expanding Beijing’s presence in Tehran’s “banking, telecommunications, ports, railways and dozens of other projects.” In return, Iran is to provide regular and “heavily discounted” supply of oil to China for 25 years, the latter projected to spend $400 billion during this period on projects in the former. Iran says Chinese President Xi Jinping first proposed the deal during a visit in 2016. The immediate reason for the deal was reportedly India halting funds for Iran’s Chabahar project because of “pressure from the United States.”

According to The New York Times, there are nearly 100 projects planned, including airports, high-speed railways and subways, effectively touching the lives of most Iranian citizens. China would also develop free-trade zones in Maku, in northwestern Iran; in Abadan, where the Shatt al-Arab river flows into the Persian Gulf, and on the gulf island Qeshm. China would build infrastructure for 5G telecommunications network in Iran.

India pulled out of Iran in line with America’s latest sanctions. The Congress Party Maharashtra in India reacted to this shift with disappointment: “With deep disappointment we at Maharashtra Youth Congress note India’s dwindling interest in Chabahar Port under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, as he has let down our Iranian allies on co-funding critical railway links, losing sight of the national interest while placating the United States of America. Iran’s Chabahar Port helps us in India safeguard the interests of landlocked Afghanistan and our bilateral relationship. Chabahar is an important access route to the sea and to world trade for our close ally and helps it resist pressure from Pakistan and China.”

The statement also contained this significant line: “As you know, India’s investment in Chabahar was a gesture of our friendship with Iran and also an endeavor by our nation to counterbalance China’s use of deep sea port Gwadar in Pakistan for our defense purposes.”

In 2009, Pakistan’s Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee Gen. Tariq Majid told a visiting British chief of defense staff that the Pak-Afghan border must be sealed on Kabul’s side to prevent cross-border movement of terrorists and weapons. Pakistan then began to fence the Durand Line. The fence is now halfway finished, and has cost the lives of many soldiers guarding against the Taliban targeting it from Afghanistan; likely funded by a regional state taking advantage of the mercenary nature of the Taliban. Significantly, the 2,430km long fence would also block off the Iranian border, from which Pakistan has been receiving terrorist trespasses that primarily target Pakistan Army personnel.

Terrorists have used the Iran-Pakistan border to strike inside Balochistan, exacerbating Pakistan’s trouble with Baloch rebels. Iran’s close relationship with India, meanwhile, has contributed to the latter’s involvement in insurgencies inside Pakistan, as was proved by the 2016 capture of an Indian spy in Balochistan. The scandal of Lyari gangster Uzair Baloch has also revealed connections between Iranian intelligence and rebel forces.

Unfortunately, Pakistan’s officially ignored sectarian violence has compelled Iran to allow terrorist elements to take shelter there, looking the other way as India exploits the weak-border situation. In consequence, Pakistan’s Afghan policy has made little headway in the face of growing Indian presence there via the Chabahar highway.

In June 2020, four gunmen attacked the Pakistan Stock Exchange in Karachi, killing three guards and a policeman and wounding seven others before being shot dead. It was soon discovered that the terrorists were militants from the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) that in 2018 had stormed the Chinese consulate in Karachi, killing at least four people, and had also attacked a five-star hotel in the port city of Gwadar in Balochistan. One can see here the exploitation of the Baloch disturbance to carry out acts of terrorism aimed at Pakistan and China.

The big change in Iran after its project-based close relationship with China would lessen India’s pressure on Pakistan and might even persuade New Delhi to initiate the process of normalization with Islamabad. India would have to turn its attention to the Gulf region, where it competes with China for economic dominance in the region. The importance of Gwadar for China would also increase after the oil deal with Iran, as would the timely completion of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and the development of infrastructure within Pakistan that the country lacks the capacity to maintain effectively. This means that China would have to be more deeply involved in the completion of CPEC. Any increase in the Chinese control would go in favor of Pakistan because of the latter’s difficulties of governance.

The closure of the Chabahar option for India would greatly affect Delhi’s influence in Afghanistan, which in turn would lessen the pressure on Pakistan to deal with cross-border Taliban attacks. This would lead to reduced pressure from disaffection in Pakistan’s tribal areas, where long years of neglect have driven the population to street protests. Pakistan has “revealed” that some of these groups from the tribal areas have been in touch with Indian agents across the Durand Line. With China compelling Iran and Pakistan to work closely for CPEC—and switching off their sectarian squabbles—the trouble in Pakistan’s north would also likely subside.

Iran, with its high literacy rate, would benefit from the Chinese-funded projects more than Pakistan because of the poor quality of Pakistani manpower. As Pakistan becomes more secure after the exit of India from Iran its poverty of governance would come to the fore, compelling China to engage more intrusively in the completion of CPEC infrastructure projects. This might mean more effective control over the Gwadar port, now destined to become the most important port in the region. Fortunately, the Pakistan Army has behaved with more strategic flexibility in recent times and would encourage Islamabad to redouble its efforts to normalize its relations with India, focusing on trade over ideology.

Lest we forget: India and China might be involved in a faceoff in Ladakh, but they still have a two-way trade worth $85 billion. For cash-strapped Pakistan, this would be a deal too good to ignore.