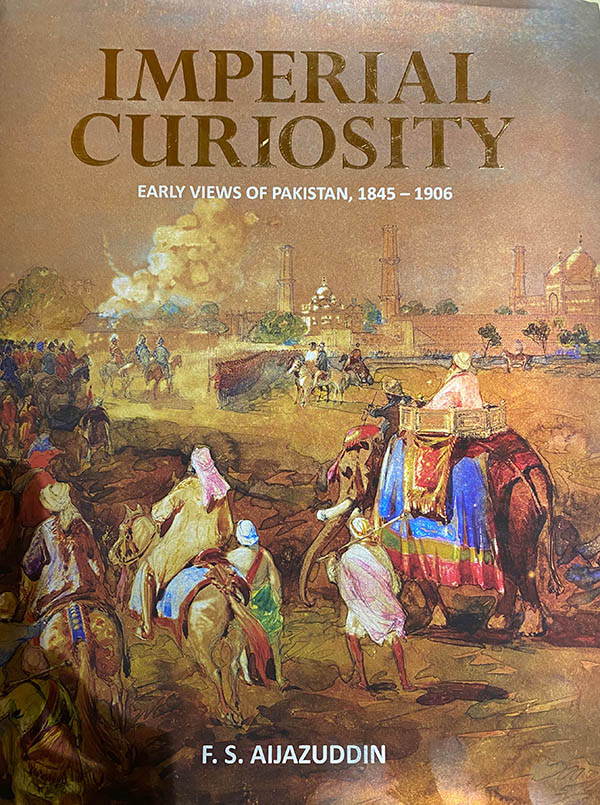

The cover of ‘Imperial Curiosity’ by F.S. Aijazuddin

In his latest book, author F.S. Aijazuddin has compiled a valuable collection of the British Raj’s views of the lands that now form Pakistan

F.S. Aijazuddin’s latest book, Imperial Curiosity: Early Views of Pakistan (1845-1906), compiles in his inimitable style the most remarkable collection of writings, sketches, paintings and photographs on foreign visitors’ perception of pre-Partition India. It serves as a valuable record of visits to India by the artists of Great Britain patronized by the Royal Family, and the memories they left behind on the region that is today called Pakistan.

“The idea for this book came about after I read that Czarevitch Nicholas, then-heir to the Russian throne, had visited Lahore in January 1891,” Aijazuddin writes in the Preface. “I discovered material on the visits by other heirs apparent to Lahore and to other cities in this area—by the British Prince of Wales Albert Edward in 1875-6, by his elder son Prince Albert Victor in 1890, and his second son Prince George in 1905-6. These royal visits were in the nature of study tours to allow future monarchs to familiarize themselves with the empire over which they would one day rule. Each royalty, I discovered, had included in his entourage a person whose responsibility it was to keep a record of the journey. No sooner had the visit ended than a souvenir book would be prepared and published. These provided an authentic narrative of the tour. Despite being rare and out of print (or perhaps because of that), I was able to find digital copies of these books on the internet.”

After conquest, the act of ‘knowing’

In the 1840s, after having dominated most of the Indian peninsula, the British turned westwards, annexing first Sindh in 1843 and then, after the first Anglo-Sikh war of 1845-46, into the Punjab, completing its annexation in 1849. As one historian of the British Raj put it: “The subcontinent of India thereafter became a manageable entity, brought to order by British method; on the ground, first to last, it was a pungent, virile and gigantic muddle, kept in hand by British bluff.”

In 1844, Henry Hardinge went to India to assume responsibilities as its governor-general; he was accompanied by his son, Charles Hardinge. The governor general’s entourage paid a formal call on the juvenile Maharaja Duleep Singh: “The little maharaja sat next to me and was covered with jewels for the occasion, having the Kohinoor on his arm—a diamond said to be worth a million. He is a very intelligent boy, and I cannot help feeling the greatest interest in his fate. He is a nice little boy, but being fattened by butter, looks a little plethoric.”

Simpson’s rise from simplicity

William Simpson (1823-1899), the next visitor, had every reason to feel disadvantaged. Born in imperative poverty in the bleak city of Glasgow, he had no particular talent but wished to be an engineer. Instead, he learned art by copying the works of J.D. Harding, and by drawing from nature. Over the years, through sheer hard work and application, he earned a well-deserved reputation as one of the most respected illustrator of his time, dining with Queen Victoria, who collected his works, and members of her royal family.

He wrote: “In Lahore there was a very grand Durbar. About 300 Sikh sardars, or headmen, were received by the governor-general. There were no great rajahs in the Punjab, but numbers made up for greatness. The sardars were all gathered on horseback on the maidan outside the fort, with Mr. Temple, the commissioner, in charge of them. They were got up in their finest costumes. When Mr. Temple, on the approach of the governor-general, waved his hat, and led them onward, it looked like a garden of flowers in motion. At the door of the Durbar tent I saw the shoes of those within, and the heap looked as if a cartload had been tipped at the spot. After dinner we all started on elephants to see the tamasha, or fete.”

Glimpse of Kipling’s Lahore

In June, Simpson crossed the river Indus at Attock using the boat bridge. The bridge of boats was still standing—it was due for demolition—but the water level was high, and hissed fiercely as it swept down. He passed the Nicholson monument and reached Jhelum, from where he caught the 10:30 a.m. train to Lahore, which he reached at 5:30 p.m. He was able, according to his diary, to contribute a short piece for the Civil & Military Gazette on the recent campaign and went for a drive to see Chauburji and the zoo, where he was intrigued by a lukkar bagga or hyena (“very ugly”).

He remained incapacitated for the next day or so, but recovered long enough to make a quick visit to the museum and the adjacent Mayo School of Arts. He left that evening by train via Ambala and Allahabad, reaching Bombay. Before leaving Bombay, he attended the unveiling of a statue of the Prince of Wales, sketched it the next morning, and later on the same day boarded the steamer Mongolia for the three-week journey back to London. Reaching London early in the morning, he caught a cab and, with punctilious diligence, reported his return at the Illustrated London News office.

Lord Weeks’ verdict on Karachi

Another visitor, Lord Weeks (1849-1903), describes Karachi with disappointment: “It was almost with regret that we sighted the low sand hills of Kurrachee, and steamed up the narrow canal among the uncouth iron monsters cranes, rattling team-dredges, and shunting trains of freight cars. In the deafening roar from the mob of Indians and Parsees which now invades the deck it is almost impossible to take leave of our friends, the officers.

“There is a momentary glimpse of the Beloochees, rallying round their chief, now armed with their guns and ‘tulwars’, which had been restored to them. And we descend into a lateen-sailed boat, which takes us to the iron sheds of the custom–house.” There, Weeks’ luggage is examined in the great iron sheds at the landing, where the examination, although rigid as a matter of form, is lenient enough except in the matter of “liquors and fire-arms.”

Karachi vs Bombay

Lord Weeks observes: “Aside from the fact that Kurrachee is a rapidly growing port and a distributive center, expected by its sanguine citizens to leave Bombay far behind, there is little to interest the stranger beyond its winter climate, which is a shade cooler than that of Bombay. One does not need an overcoat and there is no chill at sundown or in the morning air. Away from the crowded hive where the native population quarters itself, and which has much of the teeming and dirty picturesqueness of similar sites in Bombay, as well as the same close and musty odors, the European city, if wanting in the architectural magnificence of Bombay, is at least planned and laid out on the same generous scale as regards space.”

At last, after a long dry day’s journey, Weeks reaches Lahore: “It is night when the train runs into the great fortress-like station of Lahore, built with an eye to possible military necessities; the arching expanse of glass roof, and the multitude of gas-jets twinkling dimly in the smoky gloom suggest a somewhat reduced edition of Charing Cross Station. This chance impression is strengthened by the brilliantly lighted newsstand and book-stall of Wheeler & Co., well furnished with light literature. And by the nickel-in-the-slot machines. But there is a note of piquant contrast in the three tall Indian falconers, with great buzzard-like lawks, nearly as large as eagles, which strugglingly balance themselves on the shoulders or turbans of their masters who stand on the platform environed by portentous piles of bedding.”

An Open Restaurant in Lahore, painted after Weeks’ first visit to Lahore in 1888

At the Lahore Railway Station

“A few Europeans are pacing the platform in heavy long overcoats. Upon the steps of the bridge which crosses the tracks to the other side of the station a party of “Rewari” ladies, with plump brown arms incased in rings of glittering metal, with swinging skirts and heavy anklets, richly costumed and pungently perfumed, are stooping down, intent upon scraping up a mess of some brown, greasy edible which they had spilt upon the steps. A railway official in uniform is conversing with the mob of third-class native passengers carrying strange packets of every conceivable shape; they are confined like prisoners behind the cross-bars of a strong wooden grating, and presently, when the train is ready the official turnkey will let them loose.

“So intermingled are Europe and Asia that it is not easy to determine which is the discordant note—this underground railway British book-stall, and the sign of Bass’s Ale, or the hooded hawks and the brown ladies with the tinkling anklets. Outside the station carriages are numerous, and you may go to your hotel shiveringly in an open barouche labelled ‘first class’, or get into a shigram, which closes like a coupe, but is labelled ‘second class’, avoid the risk of a chill, and court the risk of being turned away from the hotel ‘for want of room’, as every hostelry is crowded at Christmas-time.

Wazir Khan Mosque

“From a cavernous arch at the end we emerge into the square facing the mosque of Wazir Khan like the great palace at Ispahan. It contains little to remind one of Europe, and the transition from the trim avenue, the horse-cars, and the red pillar post-boxes at intervals is strangely abrupt. The mosque is almost purely Persian, but for the two jutting windows on each side of the tall and deep recess above the entrance. The entire front of the gateway is a brilliant mosaic of the kind known as “kasha-work,” and the four massive towers, as well as the façade of the inner court, repeat the same scheme of blue and yellow and faded green.”

Weeks does not give the date he quit Lahore for Amritsar. He comments on the similarity between the two cities: “It is seldom that two cities of almost equal size and importance, such as Lahore and Amritsar, are placed so near together, for the distance between them is but 30 miles. Amritsar, being the cathedral city of the Sikhs, is in its way a great religious center, as well as an important commercial entrepot. It is the city of polemics, and is often chosen as a tilting-ground where wordy tournaments take place between the professors if diverse creeds, where those who have gathered to discuss in a spirit of calm and temperate investigation the merits of each respective faith, often end in fierce controversy.’

Enter Prince Albert, the Prince of Wales

Prince Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, had to carry the burden of his father’s name for the duration of his mother’s life. She wanted all her male descendants to include “Albert” as part of their names. Until and even on the day of her death on Jan. 22, 1901, to her he remained “Bertie.” He visited India in October 1875.

He noted: “Lahore looked its best in the bright light of early morning as the special train slid up to the red cloth where the Governor of the Punjaub and the Military and Civil Staff of the Province, with a very large assemblage of Europeans, were waiting on the platform of the Railway Station which, ornamented with turrets and battlements, looks as though it aimed at being mistaken for a fortification.” The Prince’s cortege made a sweep round the town, passing the encampments of the Rajas of the “Punjaub.”

Lahore and its Raja

“Lahore has not increased in magnitude or in prosperity since it came under our rule; but it was decaying before Runjeet Sing gave it importance as the seat of his newly-established empire. Certainly if Lalla Rookh were to visit it now she would see nothing at all like what met her eye in the poet’s dream, where ‘mausoleum and shrines, magnificent and numberless,’ affected her heart and imagination, and where earth appeared to share equal honors with heaven.

“The engines which scattered showers of confectionery among the people in the public squares are replaced by the locomotive scattering hot ashes and pouring out steam at the station; the chariot of the artisan, adorned with tinsel and flying streamers to exhibit the badges of his trade, is now represented by a bullock-cart.” As to the great antiquity claimed for the city, some doubts are entertained by the writer of the capital little guide-book prepared for the Prince’s visit. But the city, in his opinion, must have been founded between the first and seventh centuries of the Christian era. It was not till the reign of Akbar that it attained its highest position as the center of municipal activity: “Jehangeer was fond of it as a residence, and fixed his Court here in 1622. He was, however, at Ajmere when he received Sir Thomas Rowe [Roe], an emissary from King James I.”

Re-enter Albert ‘Victor,’ the Prince of Wales

Known in the royal family as “Eddy”, Prince of Wales Albert Victor (1864-1892) could be described as a recurring disappointment to everyone—his grandmother Queen Victoria, his father Prince Albert Edward, and his tutor I.N. Dalton, who described him as having an “abnormally dormant” mind. To everyone, that is, except his doting mother Princess Alexandra.

In Lahore, on Feb. 3, 1890, the prince laid the foundation stone of the new museum building, designed by Bhai Ram Singh with input from J. Lockwood Kipling who would be its first curator. He also opened the new Town Hall, “which had twin towers, windows in the Moorish shape and the words TOWN HALL written enormously in English and Urdu in the middle.” He shared his name with the new ward being built at an expanding Mayo hospital—Albert Victor Ward—before leaving Lahore, as a contingent of Pathan dancers gave him a demonstration of their energetic prowess at nearby Muridke.

Woodcut engraving of Bamiyan Buddha, derived from a drawing by William Simpson

Including Czarevitch Nicholas

In 1890, Czarevitch Nicholas as heir to his father Czar Alexander, paid a visit to Lahore. He noted that “Lahore, of course, is picturesque enough with its Oriental coloring, but to say anything special about it is somewhat difficult unless we note that the streets are narrow, while the lanes seem to be simply an impassable wilderness. The inhabitants are identical with our Trans-Caspian natives and Sarts-Uighurs, and, as one moves through the Black Town, one might well fancy oneself back in one’s native land.

“And how. The townsfolk, among whom one often sees the characteristic figures of Bokhara merchants and Turcomen, resemble the people of our Central Asia. Since Lahore or rather Lohawar, the Sanskrit Lohawarana, was founded, according to tradition, by Loha, the son of Rama, a current Iranian and Turanian racial influence and culture has been steadily flowing through the Punjab into India. Is there anything wonderful, then, in the visible results of this tide of foreign Turanian life, which, it may be remarked, acted it that time with equal force upon Russia?”

The King-to-be in Lahore, 1905

From the station, the royal party rode along the north wall of the old city, past Taxali gate and the Town Hall, along the Mall to Government House. By far the most interesting episode of the progress was the drive through the camp of the Punjab Chiefs assembled in Lahore to receive the Royal visitors:

“Here were the Chiefs of Patiala and Bahawalpur, of Nabha, Jhind, Kapurthala, Malerkotla, Chamba and Suket. The gathering of their retainers brought back memories of Udaipur and Jaipur and Bikanir. One seemed to stride unconsciously from the India of the railway station, of these broad roads and modern buildings, into the India of at least a century ago. For here we had wild frontiersmen with hooked noses and eagle eyes, and unshorn locks tumbling over their shoulders. Mounted on scraggy ponies; elephants in silver mail, bearing golden and silver howdahs; and dancing horses caparisoned in tinsel. Smart Imperial Service Infantry stood guard over the palanquins and palkis and in line with household troops with muzzle-loaders and flint-lock guns.”

Finally, Rudyard Kipling’s Lahore

Another account of the visit reads: “In the afternoon. Princess Mary visited the Museum and the Mayo School of Art. Readers of Kim will recall the treasure-house that enthralled the old Lama who sought the lost river, and the donor of the horn spectacles which the gentle Buddhist used with such unfeigned glee. In this chapter Rudyard Kipling sketched the Lahore Museum, of which his father J. Lockwood Kipling was for many years curator, and the cannon Zamzama under whose shade Kim and the Lama met still stands sentinel over the courtyard.”

In the afternoon, the Prince paid a private visit to the Aitchison College, where the Cadets of the Punjab Ruling Houses are educated on a plan modelled on the English public school system, and the Princess held a purdah Party at Government House.

Warriors of Peshawar

“Among these taciturn men who crowded on the house-fronts were a lot of Banias or Marwaris of Bombay and Calcutta, but real fighting men, keen traders today, pot shooting over the border at some ancient enemy tomorrow, perhaps wild beasts of Ghazis or out against the Raj before the sun is much older. Who knows? The Ghor Khattri, where the chiefs were received, was the residence of the stout Italian adventurer Avitabile who held Peshawar in his iron grip in the forties,” is written of their Royal Highnesses’ reception at Peshawar.

“In this stronghold Avitabile and his Sikhs were half besieged, and never dared ride forth without an escort of hundreds of soldiers; but the old men who remember Avitabile’s weekly assizes still speak of their master with the admiration of a troop of jackals for a tiger. The Chiefs gathered here embraced every name conspicuous in the stormy life of the frontier for quarter of a century. Even the scarlet-robed retainers calmly assisting at the garden party were armed against possible assault.”

And Sandeman on Balochistan

A perceptive final passage: “His Royal Highness received formal visits from the Khan of Kelat and the Jam of Las Bela. The conditions have markedly changed since Sir Robert Sandeman, working through the Khan, pacified Baluchistan with a facility that made his administration a subject for puzzled admiration. In their most desperate feuds the Baluch tribes owned a certain shadowy allegiance to the Khan, which Sandeman, with his intuitive perception, turned to profit.

But the man through whom he worked, and who was devoted to him with a quite touching affection, was deposed for an act of savagery, and the Sirdars now look to the British Government with the confidence Sir Robert inspired. Still, his successor is a figure amongst the Indian feudatories, controlling a mountainous kingdom ten times the size of Switzerland, and he paid his homage in full state, but with an escort of native cavalry instead of his own picturesque horsemen.”