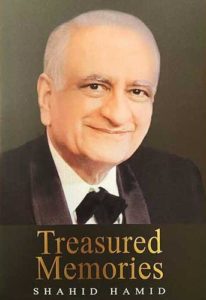

Shahid Hamid and his wife Sarwat. File photo

‘Treasured Memories’ not only recounts Pakistan’s history, but also offers an enticing glimpse into the personal history of author Shahid Hamid

In a column for The Observer, Oscar Wilde noted that “a love letter is as much about the person it is addressed to as it is about the person writing it.” Shahid Hamid’s Treasured Memories reads like a love letter to a life well lived, a family much loved and a country well served; it is as much a sociopolitical recap of Pakistan’s past as it is an insight into the personal life of one of the most charismatic and successful Pakistani men I have had the good fortune of knowing as a friend for nearly 50 years.

In a column for The Observer, Oscar Wilde noted that “a love letter is as much about the person it is addressed to as it is about the person writing it.” Shahid Hamid’s Treasured Memories reads like a love letter to a life well lived, a family much loved and a country well served; it is as much a sociopolitical recap of Pakistan’s past as it is an insight into the personal life of one of the most charismatic and successful Pakistani men I have had the good fortune of knowing as a friend for nearly 50 years.

Treasured Memories is many things. But while a very handsome book, it should not be mistaken for an autobiography, as I see it as a slice carved out of a larger picture. Most autobiographies are inspired by a creative impulse to select only those events and experiences in the writer’s life that help build up an integrated pattern. In this respect, the autobiography is also like a photograph as a means of identity construction. The difference, of course, is that an autobiography explores the relationship between identity and narrative, while the photograph leans towards identity and a specific visual. In Treasured Memories, with Shahid’s portrait on the book cover, we have both.

One of the most notable literary critics of the 20th century, Northrop Frye, opines that the autobiography is characterized by its conscious effort to create a protagonist. There is no apparent reason why that should be cause for alarm, except that one must guard against a self-serving motive; this is why I prefer the descriptive phrase “life writing” for this book.

The history of life writing as a genre reflects selfhood, as it works in tandem with the rise of individualism, gaining cultural value by linking itself to profound questions concerning self-awareness, self-analysis, and performance. The romantic period in literature responded to this by linking the relationship between the self and life writing to form a new cult of the author—making it sound almost like a self-styled confessional. For the critic, this genre has created a fascinating new form of study as one’s own story was seen to be dependent on another’s. Such writings negotiate precariously since they emphasize an important basic element of the life narrative: i.e. fulfilling the reader’s expectation that whatever has been written is true.

Shahid traverses the terrain between the ontological gap of identity and temporality with great finesse in a narration which is neither wayward nor loose, but crisp and forthright. His voice remains matter of fact, his gaze intimate as well as penetrating; resulting in a narrative replete with details of places, people and issues that come alive. Especially noteworthy are his reflections on the personal history of his family, as well as a more impersonal national history; Shahid is careful to dismantle any enhancement of his own personae. The protagonist’s voice therefore is clearly Shahid’s and, more importantly, there are people still living who can vouch for the veracity of his writings.

Memories offers a wide variety of fields for further enquiry and debate. It not only fulfills the promise of a good read—the narrative voice is direct, forceful, and precise with an occasional hint of laughter lurking between the lines—but also provides a mélange of facts both public and private. At times it almost reads like two books in one: one narrative covering matters of grave national importance, and another that is an anecdotal history of a blessed life.

However, what struck me most about Treasured Memories was not so much the breathless pace at which Shahid describes and details Pakistan’s history, including the dismissal of Benazir Bhutto’s government to name one incident, but rather the realization that Shahid had played such a pivotal, yet discreet role in drafting documents of national importance, parleying with former and present rulers; doing a balancing act vis a vis the men in khaki and those in mufti; all the while paying back with his quiet philanthropy to the country that has given him so much.

The facts laid bare in Memories draw a parallel between Shahid’s recounting and the secret of Queen Elizabeth I’s successful 45-year reign—knowing when to keep her mouth shut while ascribing to the motto video et tacio. Well-read and knowledgeable, Elizabeth spoke little, laying the foundation of the British empire and lending her name to an entire era—the Elizabethan age. Shahid may not have an epoch named after him but any Pakistani reading Treasured Memories is sure to come away with gratitude for his erudition, good sense, constitutional expertise and adherence to the rule of law during the many years he served the country at both the federal and provincial levels.

Particularly fascinating is Shahid’s Bangladesh nee East Pakistan odyssey. I had the privilege of accompanying my father, the late Chief Justice S.A. Rahman, while he was presiding over the Agartala Conspiracy case. My summer in Dacca was an experience I find difficult to forget and Shahid’s detailing of life at its most elemental level in the rural districts of East Pakistan brought home the poignancy of separation once again.

Beyond its historical importance, the book is also a great read on several levels: as a woman, I am immensely gratified to note how often Shahid references consultations with his wife, Sarwat, whose opinion he clearly values; as a concerned citizen of Lahore, I also feel that Shahid and Sarwat’s stay at the Governor’s House will be long remembered for Sarwat’s painstaking restoration attempts, as well as the air of elegance, grace and dignity that the couple brought to the historic residence.

As an educationist, I can vouch for Shahid being one of the most proactive chancellors that I have had the pleasure of seeing in action during the half century I have spent teaching future citizens of the country. He was the first chancellor, for example, to draw attention to the enormous network of ghost schools that the Punjab Education Department had been running with impunity under the very nose of various provincial governments. Needless to say, action was taken immediately.

One of the points that took me by surprise while reading Treasured Memories was that Shahid professes to be apolitical in the popular sense of not being a registered member of any political party. With due apologies, I view every human act—be it the arts, performance, writing, music or an opinion—as a political statement, perhaps not aligned with any party’s manifesto but a political act nevertheless. In writing Treasured Memories, Shahid aligns himself publicly with the Pakistanis for whom Pakistan, its Constitution and the rule of law takes priority over all else. Similarly, he aligns himself with the men who prioritize family, love of child and parent, gender equality, equal opportunity and the right to happiness for all.

Apart from the readings in memory, the book presupposes that the reader will be familiar with the people and events it recounts. The roster of names that comes pouring off the pages is a moving reminder of an ‘old Lahore’ when everyone knew everyone else. I do not remember when I first met Shahid—it was likely at a dinner party—but our association also dates back to a previous generation as my parents and his, particularly his mother, were old acquaintances. Such are the truly unpredictable intersections of life.

In his Epilogue to Treasured Memories, Shahid pinpoints a number of issues that have plagued our country from its birth. From a massive failure to control population growth to the travails of a badly mauled economy; from low education indicators to flawed policies regarding the failure to empower elected local governments, Shahid lists the imperatives needed for a stable, prosperous Pakistan. Recognizing that past history is replete with more failure than success, Shahid continues to hope, as he says himself at the end of the book:

“I am an optimist, always have been. The path will be long and arduous but Pakistan will prosper insha’allah!”

Given global conditions, optimism itself is a fierce political act. But one must distinguish between the “unthinking optimism” of those who believe that “it will all work out in the end,” which is nothing but an excuse for inaction; and the unthinking pessimism of those who bemoan a “we are all doomed” mantra.

I would opt for the kind of true optimism espoused by Shahid, which is neither foolish nor silent, yet can be revolutionary. Great movements for social change always begin with statements of great optimism. When no one believes in a better future, despair is a logical choice, and despairing people almost never change anything. When no one believes that a better solution is possible, those benefiting from the continuation of a problem feel safe. When no one believes in the possibility of action, apathy becomes an insurmountable obstacle to reform. But introduce intelligent reasons for believing that action is possible, that better solutions are available, and that a better future can be built, and you unleash the power of people to act out of their highest principles. Shared belief in a better future can be an explosive force in politics for it is the strongest glue there is to forge a unified nation—and that to me is the philosophy at the heart of Treasured Memories.

Shahzad is an actor, educationist and writer, and recipient of President’s Pride of Performance award for Literature.