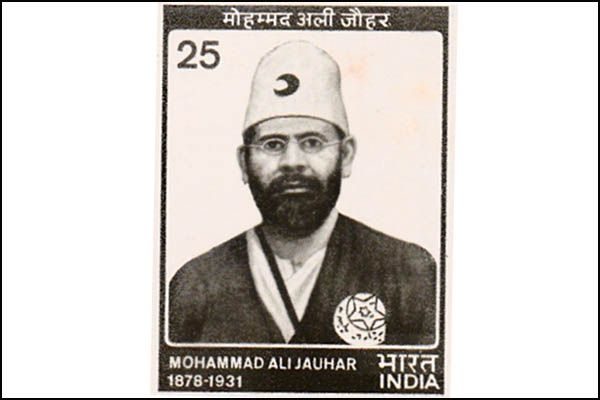

India, in 1978, marked the centenary of Muhammad Ali Jauhar’s birth with a commemorative stamp to celebrate his service toward building Hindu-Muslim unity

Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar, who led the Khilafat Movement, backed agitational politics and was often at odds with his contemporaries

Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar (1878-1932) led the Khilafat Movement, the largest political drive in India, and is today also featured in Pakistani textbooks as one of the leaders of the Pakistan Movement. Professor M. Naeem Qureshi, in his insightful book Ottoman Turkey, Ataturk, and Muslim South Asia (OUP 2014), highlights the role of the maulana in the Khilafat Movement, retaining the original spelling of ‘Mohamed Ali’ without ‘Jauhar.’

When the Ottoman Empire was threatened by western encroachment, reverberations in Muslim India were prompt and intense. This reaction reached its climax after the First World War, when the Ottoman Empire was to be parceled out among the “victors.” In December 1918, the famous Khilafat movement of India began “to save Turkey from the ignominy of spoliation.”

The movement was born in the embryo of the All India Muslim League (founded in 1906). But, soon, a separate body, known as the Central Khilafat Committee, was formed in Bombay under wealthy businessman Seth Jan Muhammad Chotani to concentrate solely on the Turkish issue. Fireband clerics Maulana Mohamed Ali Jauhar, and his elder brother Shaukat Ali, later took over the movement and organized it—all while undergoing the rigors of British captivity for their pan-Islamic exuberance since 1915.

Khilafat Committee in London

The Committee decided to go to London and plead its case for the Turkish Khilafat. The leader of the delegation was none other than Mohamed Ali Jauhar, the fiery journalist-politician who had, in 1913, led a two-member delegation to Britain to secure redress in the famous Kanpur Mosque affair. Educated at Aligarh and Oxford, Mohamed Ali had a brief initial career in the states of Rampur and Baroda before embarking on a brilliant journalistic venture. He edited two well-known journals of Indian opinion, the Comrade and the Hamdard, which were later banned for their pan-Islamic fervor; the editor was interned at Chindwara along with his elder brother Shaukat Ali.

Prior to the delegation’s departure for Europe, Jauhar, accompanied by brother Ali who had become the most powerful leader of the Khilafat Movement as the Committee’s honorary secretary, undertook a whirlwind tour of the principal centers of political activity in northern India to raise funds for the delegation’s expenses. They were given rousing receptions in most places, particularly in Delhi, but the amount of money collected by them fell considerably short of the target of one million rupees despite both brothers contributing the entire sum of money presented to them at public meetings for their personal use. Nevertheless, in February 1920, the Khilafat delegation left Bombay for Europe by the Italian steamer S.S. Hungaria.

On board the ship, Mohamed Ali Jauhar tried to learn spoken Arabic and Sulaiman Nadwi occupied himself by taking English lessons as he was not fluent in the language. Syed Hossain kept himself busy with his books. On their arrival in London, the members of the Khilafat delegation went straight to Parliament where a debate had been forced in the House of Commons by anti-Turkish circles against the Supreme Council’s decision of Feb. 14, 1920 to leave Istanbul with Turkey. It was in such an atmosphere that the Khilafat delegation began its work in London.

Jauhar’s clash with reality

Mohamed Ali Jauhar’s early optimism about the success of his mission vanished upon coming face to face with the prevailing realities. Moreover, the delegation’s personnel, especially its leader, had come under attack from various quarters, including some members of Parliament. No doubt, Jauhar led a weak delegation. Nadwi knew very little English and the proceedings had to be interpreted for him; Hossain was constantly sulking over a broken love-affair with Motilal Nehru’s daughter, Vijaya Lakshmi; and Abul Kasem and Kidwai had yet to join him from India—but most of the criticism was unwarranted. However, Mohamed Ali was not dejected and started working with whatever support he could muster, particularly in cooperation with Syed Ameer Ali and M. H. Ispahani of the London League, B.C. Horniman (1873-948), the erstwhile editor of the Bombay Chronicle, Sarojini Naidu (1879-1949), who was then visiting Britain; and other Muslim associates.

Through his previous experiences in Britain, Jauhar knew that the success of such missions depended on good contacts and sound propaganda. But the difficulty was that Marmaduke Pickthall had lost all interest and he was away from London most of the time. This had become necessary since The Times and other notable publications had refused to publish even their well-paid notices. An opportunity was found very soon when Mohamed Ali bought £10,000 worth of shares of George Lansbury’s Daily Herald, which had been founded in 1911 as a strike-sheet but had survived to furnish an outlet to Syndicalist views. These efforts resulted in modest success and the delegation’s activities began to be noticed. In its work, the delegation also found the willing cooperation of some Indian students, including Abdur Rehman Siddiqui, Shoaib Qureshi, and Muhammad Habib.

Jauhar asserted that, in consonance with the religious requirement, the caliphate should be preserved with adequate temporal power and the caliph should retain his control over the Jaziratul-Arab and the wardenship of the Holy Places and sacred shrines. He argued that if the caliph retained his control of the Jaziratul-Arab, and if the pledges of the British prime minister and of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson were redeemed in their entirety, the restoration of the territorial status quo antebellum would automatically be achieved.

Hindu-Muslim unity over Khilafat

Reasonable guarantees could be taken for the autonomous development of all communities, whether Muslim, Christian, or Jewish. Jauhar did not hesitate to state that their allegiance to God and Islam’s Prophet took precedence over any allegiance to an earthly sovereign. Ali was joined by Hossain and Nadwi in stressing a point that for them, and for the Indian Muslims, the question of the Khilafat was purely religious and not a political issue. Hossain pointed out that Hindus had joined the movement because they had come to regard the Khilafat issue as a national rather than a sectarian question.

After the meeting, a cleverly edited summary of the proceedings made the demands of the delegation look ridiculous while the prime minister’s opposing arguments were made to appear flawless. The India Office cabled this summary to the viceroy without the knowledge of Ali, who was given a copy only after its publication. This one-sided story was then spread widely through the Reuters’ seemingly reliable messages. Ali was angry at this deliberate twist but was helpless.

A skeptical Gandhi

In March 1920, a meeting was hastily convened at Ajmal Khan’s residence in Delhi, which was attended by all the prominent leaders, including Abdul Bari, Shaukat Ali, Abul Kalam Azad, M. K. Gandhi, B. C. Tilak (1856-1920), and Motilal Nehru. A secret session on the sidelines of the meeting also discussed non-cooperation with the government. Pressure was put on Gandhi to proceed to London immediately and, without prejudice to Ali’s delegation, place prevalent Hindu-Muslim feelings on the question of the Khilafat before British ministers and the public. But Gandhi, perhaps realizing the futility of the measure, was reluctant to proceed to Britain unless he was assured that public opinion was generally in favor of sending another delegation abroad and that it also had the permission and approval of the viceroy.

Nevertheless, Gandhi’s hesitation had created misgivings among some of the Khilafat supporters, particularly Azad, who had begun to suspect his motives. The suspicion, however, did not last long as Gandhi soon plunged himself vigorously into the Khilafat Movement.

Optimism of Khilafat Movement

Azad, Mushir Kidwai and, above all, Bari appeared to have passed hasty judgments on the performance of the delegation. Even a moderate like Mohammad Iqbal, who was idolized by Mohamed Ali, was moved to ridicule the “begging bowl” of the delegation. Indian Muslims residing in Britain were also reported as being reluctant to offer further support. They seemed particularly embarrassed by the prime minister’s arguments regarding Ali’s disapproval of Arab desire for independence. Syed Ameer Ali was among those who displayed, though only temporarily, a sign of irritability.

But, despite these disheartening circumstances, Mohamed Ali Jauhar decided to stay on and continue his work on the caliphate issue. By early May 1920, the delegation had fully realized that they were not getting anywhere with the British government and that their real work lay in India. And yet, they had decided to stay on and try to reach at least a section of the British public that seemed amenable.

As time passed, Jauhar’s speeches became increasingly bitter. The delegation was able to attract some attention in London but the propaganda against them was too strong to let them create any lasting impression. He also visited Rome with a desire for an audience with the Pope, who was regarded by the Catholic world as the Vicar of the Christ and the visible head of the Church at the Vatican. The Indians had realized that the effective government of Turkey was in Ankara and not in Istanbul. Mohamed Ali, therefore, approved of the tactic of Mustafa Kemal whose military prowess, he believed, would achieve what others had failed to accomplish.

First glimpse of the Taliban?

Mohamad Ali reportedly repeated to the Turks under Mustafa Kamal Pasha the suggestion of a world Muslim congress for intra-Islamic issues. Apparently, the two men also prepared an ambitious plan for the invasion of India by an army composed of Afghans, Indian muhajireen, and tribesmen on the Indo-Afghan border. The funds for organizing this force were to be provided by, among others, the Khilafat movement leaders. The Bolsheviks were expected to help launch the offensive. For the proper execution of the plan, it was reported that Talat Pasha was to move to Moscow, Enver Pasha was to go to Tashkent, and Jemal Pasha was to raise the army of invasion in Afghanistan. Mohamed Ali was expected to synchronize it with a revolt in India.

By August 1920, having failed to achieve anything regarding the Turkish treaty, the delegation seriously contemplated sailing back to India. Just then, a telegram was received from the Khilafat Committee stating that it was the opinion of Abdul Bari, Gandhi, Chotani, and other Khilafat leaders that the delegation should visit the United States for a month.

The members were divided in their opinion about the utility of their mission across the Atlantic. While Jauhar was in its favor, H. M. Hayat was non-committal and Abul Kasem and Sulaiman Nadwi were opposed to the idea. Nadwi, in particular, was of the view that the anti-Turk bias in America had taken such firm root that their visit was bound to prove ineffective. It was proposed that only Jauhar and Syed Hossain should visit the States for a month or two while the others should return to India. An angry scene was said to have followed, but in the end the idea was dropped altogether.

Abdul Latif Azmi’s view of Jauhar

Author Abdul Latif Azmi in his Urdu book Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar: Aik Mutaliya (1980) reveals aspect of Jauhar’s personality not commonly known in Pakistan. Jauhar wrote scathingly of Allama Iqbal, as he had also done of Abul Kalam and Khwaja Hassan Nizami. His writings on his spiritual leader, Maulana Abdul Bari of Farangi Mehal, may also have broken the heart of the old man near his death. Our books on journalism only passingly refer to the “fickle” nature of Jauhar’s journalism.

What is endearing in Jauhar is his sense of humor, his command over Urdu, and his complete freedom from the financial corruption so rampant in the newspapermen of his time. His brother Shaukat Ali tells us that Jauhar was incontinent in childhood, a disorder that lasted through his youth and was to complicate his diabetes later on. The brothers were brought up in an environment of extremes. Indulgence was mixed with bullying, hard play mixed with hard study. Jauhar was good at sports in his youth and a scholar of great industry in later life, although he couldn’t pass his Indian civil service exam in London. He was a scrappy individual, fighting to reform the Aligarh College of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, fighting with the British government on the issue of the Turkish caliph, and fighting with his colleagues on the Khilafat bandwagon.

He shouldn’t have locked horns with Kalam, the other panjandrum of the Movement, but he did. He shouldn’t have treated Maulana Abdul Bari, the man who started the Khilafat Movement, the way he did—Bari believed the Sharif of Mecca, the frontman of Turkey in Hejaz, was the right man as the Servant of the Ka’aba, but Jauhar supported Ibn Saud and his Wahhabi objection to the gumbud of the mausoleum of Islam’s Prophet. This brought about the rift in Lucknow, which resulted in crowds refusing to listen to Jauhar’s fiery speeches. In Delhi, Muslims were already objecting to his slavish devotion to Gandhi, but if you listened to Gandhi he had his own complaints about the fickleness of a man who otherwise thought nothing of kissing his feet.

An unstable man of passions

Although Jauhar was in the habit of writing defamatory articles—only to issue denials later—editors who worked for him vouch that he wrote his weekly essays for Comrade in English after extensive research. The articles in Hamdard were usually translations or contributed by others who imitated his style. He was extremely temperamental in behavior, bullying to the insulting extreme, then making up with hugs and copious tears of regret. But Azmi’s book brings testimony to the effect that Jauhar was more unsteady as an individual than his elder brother, who changed his personality from a ruffian (which he himself admits) to a thinking man whose time was mostly spent in patching up the quarrels started by his younger brother.

The book is balanced between the great genius of agitational politics of Jauhar and his vacillating behavior toward his contemporaries. Khwaja Hassan Nizami accused him of being jealous of his more gifted friends like Abul Kalam and Zafar Ali Khan. But what can’t be ignored is his unwavering courage in confronting the British Raj and keeping himself in the limelight with his matchless oratory. He went repeatedly to jail and his home was destroyed by his political career, but suffering never inclined him to make compromises. What he wrote might not all be temperate but it remains eminently readable because of his flowing Urdu style. He was like a blind pugilist, whose flailing blows hurt the adversary as well as the friend, but the punches were always elegantly delivered.

A generous Jinnah

It is this enfant terrible that the book brings out with great attention to referential detail. He arose to be a leader of Congress before being gratefully accepted into the fold of the Muslim League. Jinnah gave proof of his generosity of spirit by accepting his son-in-law, Shoaib Qureshi, into the new set-up in Karachi. Jinnah and Iqbal had not supported Jauhar’s Khilafat adventure and were therefore subjected to his barbs, but Pakistan has done well by owning Jauhar as a spoiled son who had many sterling qualities.

There are graves of several Indian Muslim pilgrims in Jerusalem near the Al-Aqsa mosque and Omar Mosque, which is currently under Israeli control. The first-ever Muslim graduate from Oxford’s Lincoln College, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar (1878-1931), had willed to be buried in Jerusalem instead of a “colonized” India. Hailing from Rampur and having studied at Aligarh, Jauhar had established the pioneer Asian students’ society at Oxford University, the Majlis.

Another notable Indian Muslim buried in Jerusalem apart from Jauhar is Begum Ghaffar Khan, who hailed from then-Frontier Province and died in the Omar Mosque after having suffered a concussion from a fall. She was the wife of the legendary “Frontier Gandhi,” Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890-1988), the Pashtun leader who followed non-violence and had begun political defiance even before Gandhi landed back in India.