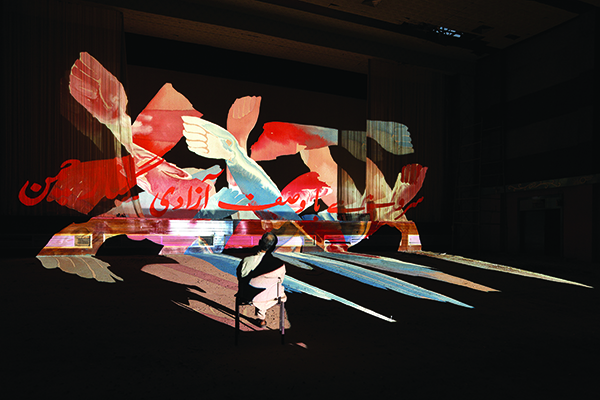

The Cypress, Despite its Freedom, Remains Captive to the Garden (2013) by Shahzia Sikander

Nationalism, censorship, and the making of a canon for Pakistani art.

“Shahzia Sikander is not a Pakistani artist because she doesn’t engage with the community,” Quddus Mirza claimed at last year’s Lahore Literary Festival. It was odd to have a hypernationalist, even xenophobic, sentiment of this kind voiced by a painter and critic, whose concerns supposedly include the questioning of nationalist ideology. Even more oddly, the same Mirza had offered glowing praise for Sikander in a national newspaper some years earlier. This startling shift of opinion may be dismissed as an example of the petty conflicts and personal resentments that mark Pakistan’s cultural elite. But it signals something more ominous in a context where “culture” has come to represent Pakistan’s only positive image to many of its own citizens as much as to art buyers and investors internationally. So what is this hastily-constructed canon of “Pakistani culture” that includes some artists but excludes others?

Sikander is one of Pakistan’s best-known artists. She was born, raised and trained in the country, whose citizenship she continues to hold, and whose history and traditions her work has consistently addressed. One wonders then what “community” it is that Mirza thinks she isn’t engaging. Perhaps it is the small and self-appointed community of artist-critics, which Mirza apparently speaks for. Indeed, Pakistan is unusual in producing critics who are also artists, which in any other profession would involve them in a perpetual conflict of interest.

What this double role allows artist-critics like Mirza, Cornell University’s Iftikhar Dadi or Chelsea College of Art’s Virginia Whiles to do is to rewrite Pakistan’s art history and even erase important figures from it. In this way they repeat, on a smaller scale, the very acts of censorship and erasure for which their work criticizes politicians and religious or military leaders. In fact their ostentatious “critique” of such violence, which is externalized in the political arena, actually permits these writers to internalize it even more effectively in the cultural sphere—and all with a seemingly clear conscience.

Among the most significant victims of such historical vandalism are Pakistan’s Unver Shafi and Sikander. I wrote about the latter’s work more than a decade ago, and given the international acclaim she has received since then need not repeat my reasons for considering her an extraordinary artist, both technically and conceptually. And yet Sikander’s pioneering work is under threat, being routinely censored by the artist-critics whose writings have made them brokers for prizes, museums, and the international art market.

In his book Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia, Dadi does not mention Sikander even once, despite writing about her peers and teachers—and even exhibitions in which she was featured. Since Sikander was the first Pakistani artist to achieve recognition globally, opening the door for others, including her artist-critics, to describe this exclusion as dishonest is putting it kindly. Similarly, in Art and Polemic in Pakistan: Cultural Politics and Tradition in Contemporary Miniature Painting, Whiles refers to Sikander’s work only very briefly and ignores its foundational character for the school of art she writes about.

Both Dadi and Whiles write art history in a genealogical style, tracing contemporary aesthetic production back to founding fathers in a comically patriarchal way. They suggest that Imran Qureshi, the Pakistani artist who painted on the rooftop of New York’s Metropolitan Museum last year, is the “father” of the new miniature, forgetting that in the 1980s and ’90s it was Sikander, working with Bashir Ahmed and Zahoor ul Akhlaq, who provided miniaturists with a new format as well as an international platform. Moreover, while Sikander fully acknowledges her indebtedness to teachers and traditions, she has broken the genealogical line not simply by garnering more recognition than any of them, but also by putting such genealogies into question in her work, which always cancels out the idea of origins.

Neither her work nor that of Shafi, with its intensely abstract character, fits easily into the crudely “political” categories that writers like Dadi have invented for Pakistani art history and which they seem to have taken wholesale from the academic chatter common in U.S. universities during the ’80s and ’90s. Here is an example from a description in Dadi’s book of his own work: “We attempted to articulate a post-conceptual practice in dialogue with the vitality of popular urban visualities to create photography, sculpture, and installations commenting on the visual theatrics of violence and urban identity and serving as an oblique critique of official nationalism.” One looks in vain for the “oblique critique” that Dadi refers to, only to be met by a barrage of obvious and stereotyped oppositions, in which such overexposed terms as “clash of civilizations” or “war on terror” are subjected to rather trite reflection.

The double role of artist-critics allows them to rewrite Pakistan’s art history and erase important figures from it.

Deploying as she does this logic of juxtaposition, the accomplished miniaturist Saira Wasim is thus preferred in Dadi’s Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia over Sikander, for whose subtlety his categories cannot account. Serving as gatekeepers for what counts as “Pakistani art,” figures like Dadi simultaneously deploy and “critique” nationalist narratives, thus helping to direct the flow of money going to support the culture of a country that has become globally visible because of its many problems. Everyone, it seems, can make money out of militancy and war, those who speak for as much as against it.

Even when lavishing praise on his chosen artists, however, Dadi is curiously unable to locate their work in the social and historical context that his book is meant to describe. Wasim’s Round Table Conference (2006), for example, is said accurately but also misleadingly to portray meetings of the Organization of the Islamic Conference; the title’s clear reference to the far more celebrated and consequential Round Table Conferences of the 1930s are left unexplored. It was in those meetings, after all, that Pakistan’s history might be said to have begun, witnessing as they did the birth of the future country’s name. Similarly, when describing the use of the number 5 in Risham Syed’s work, Dadi links it to everything—from the five senses to Islam’s five prayers—except one of the most common references in Pakistani society: that to the five members of the holy family, who the Shia, in particular, venerate. It is one thing to make Sikander disappear from Pakistan’s art history but to erase, in effect, the cultural presence of a Muslim sect under attack in Pakistan is unconscionably naive.

Minor though such exclusions might initially appear to be, taken together they indicate a systematic erasure of history. And nowhere is this more evident than in Dadi’s principal argument about “the art of Muslim South Asia,” which, it turns out, is all about Pakistan. His book foregrounds artists like Chughtai and Sadequain, whose emergence and influence cannot be understood without taking into account powerful Indian voices like S. H. Raza, M. F. Hussain and Tyeb Mehta of the older generation or G. M. Sheikh and Zarina Hashmi among the younger one. Of course, this would show up “Muslim South Asia” as a false aesthetic category, and therefore a made-up commercial label, since the artists involved clearly belong to worlds not defined by their religion. Maybe there is a critique of “official nationalism” being made in this claim for Pakistani art being synonymous with “Muslim South Asia,” but if so it is so “oblique” as to be invisible. In other words, Sikander’s banishment from Pakistani art history is not merely the result of personal animosities; it illustrates a more general and deeply worrying trend of narrowly nationalist censorship and historical amnesia among the very champions of their “critique.”

With brokers in the art world in a position to rewrite Pakistan’s aesthetic history and set the pattern for collecting internationally, the work of these Little Dictators represents nothing less than the success of the big ones they so love to inveigh against. If anyone can break this stranglehold on the narrative of Pakistan’s cultural history, it is Sikander, who achieved global fame in the pre-9/11 world and whose work is not over-determined by the “war on terror,” itself now an aesthetic commodity. But it is a sign of the damage that has been done her if audiences have to be reminded that Sikander was the first artist to grapple with the miniature as a craft-based medium and make it central to contemporary art, internationally. In this sense, all those who came after her from Lahore’s National College of Art’s miniature department are indebted to her. But such recognition has been scant. Perhaps Sikander’s appearance at this year’s Lahore Literary Festival will spur a new appreciation of her work in Pakistan, and in doing so mount the first real challenge to an art-historical narrative that mimes real-world violence through acts of erasure.

Devji is director of the Asian Studies Center at the University of Oxford. He is the author, most recently, of Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea (Harvard University Press, 2013). Sikander is LLF’s Artist of the Year. From our March 1 & 8, 2014, issue.

7 comments

Faisal Devji’s allegations are simply outrageous.

The focus of my book is on modernism in South Asia, not contemporary art. It analyzes in some detail selected work of a very small number of artists: Chughtai, Zubeida Agha, Zainul Abedin, Shakir Ali, Sadequain, Rasheed Araeen, and Naiza Khan. The contemporary artists Devji mentions are discussed only briefly in a very short (11 page) Epilogue. This certainly does not mean that I find their work to be inconsequential, but only that following a research project requires one to focus on a set of questions and an archive, and above all, to advance an analytical and conceptual understanding of aesthetics and society based on necessarily selective cultural practices and artifacts, rather than writing a broad, bland survey. For this book, that emphasis was on twentieth century practice. The word-count of the book exceeded the limit set by the publishers, and simply could not be any longer. As a result, I was unable to discuss a number of important artists such as Ahmad Pervez, Zahoor ul Akhlaq, or Shemza.

Why does the development of Pakistani art have to be conceived as a zero sum game? Is Devji seriously implying that recent awards to Imran Qureshi and Naiza Khan are undeserving? Is Sikander the sole and singular artist worthy of recognition, and is her mention always necessary in every account of contemporary art in Pakistan? If Devji finds Sikander’s work to be so significant, one wonders why he chooses to mount unbalanced attacks on the too few of us who are seriously committed to the art history of Pakistan, and not by using this opportunity to explicate the significance of her work (as by his own admission, he has not written on her work for over a decade)? Simply listing her accolades in the West and ascribing her role as a pioneer, as Devji does, is no substitute for formal and contextual analysis of actual works and projects, which will render her works aesthetically and historically meaningful. And certainly Sikander is hardly a forgotten figure, she is among the best-known artists from Pakistan internationally, a recipient of the “mother-of-all-awards,” the MacArthur. She is hardly absent from the market, represented by well-established galleries in New York and London. Precisely how is she under censorship or erasure?

For the record, I have never claimed that Sikander is (or is not) “Pakistani,” for me this kind of binary categorization is unhelpful in assessing the work of any artist. The question of the adequacy of nationalism and of “Muslim South Asia” in characterizing the works of artists in my book is important, and requires a much longer assessment than is possible here. Indeed, my entire book is a meditation on how artistic practice since the beginning of the twentieth century is a profound engagement with these frameworks. I do not see this as a settled matter: rather, these categories mark an ongoing crisis of self and society. My usage of them is also necessarily marked by catachresis, in that I have no recourse but to deploy concepts whose referent is neither adequate nor stable. It seems that Devji has not read or comprehended my book beyond the Epilogue, as its Introduction lays out the methodological stakes in addressing the vexed problem of “Islamic art” and its relation to modernity in South Asia.

I have never claimed that Imran Qureshi is “father” of the new miniature. I do note that he has “played a key role in training the next generation of miniature artists at the National College of Art” (p. 220), a role that Sikander never ever assumed. Does Devji have a different understanding of this widely established fact? And the allegation of my genealogies as being “comically patriarchal” is also odd, since I discuss Zubeida’s Agha’s pioneering work in abstraction as foundational. Abstraction as a mode of practice is a very significant for me, as can be seen in my discussion of Zubeida Agha and Shakir Ali.

On the significance of the number 5 for Risham Syed, the sentence in the book (p. 224) begins as: “The number five has multiple connotations for the artist:” making it very clear that the meanings I describe are those the artist herself communicated to me as being of significance to her. As for Devji’s outrageous accusation that I unwittingly foster sectarianism in Pakistan, this is a malicious allegation unworthy of response, especially since I discuss the foundational importance of Shiaism for Sadequain’s art (p. 161), and how Araeen’s White Stallion is also a commentary on ongoing Shia-Sunni violence (p. 197).

To the best of my knowledge, the three Round Table Conferences of the early 1930s were negotiations between British and Indian leaders, not amongst the leaders of the “Muslim World” as depicted by Wasim in her Round Table Conference.

I have tried to be very scrupulous in not making the book into a personal platform for my own artwork. Indeed, in a book exceeding 70,000 words, my work (along with the work of Elizabeth Dadi and others) is discussed in passing in exactly 83 words, and is accompanied with no images. The so-called “Karachi Pop” has been recognized by many critics as an important development during the 1990s in Karachi (which did not have a miniature practice), and which opened up a new modality of practice by subsequent artists to engage with media and urban popular culture. Is Devji seriously suggesting that I should have omitted even this brief mention, and provide no context whatsoever for Karachi during the 1990s?

I have made no work called War on Terror. As for the billboard work Clash of Civilizations (with Elizabeth Dadi): this was created in the US after September 11, 2001, a deliberately provocative response to developments within the United States at a time when I was already based there. It is emphatically not a subject of any of the arguments in the book that discuss nationalism in South Asia (but it should be noted when it was exhibited in Islamabad’s National Art Gallery’s inaugural in 2007, the work had to be re-sited in another part of the building so that President Musharraf would not encounter it upon inauguration.)

Devji writes, “the work of these Little Dictators represents nothing less than the success of the big ones they so love to inveigh against. If anyone can break this stranglehold on the narrative of Pakistan’s cultural history, it is Sikander….” I leave it to the readers to assess whether equating the work of serious scholarship with dictatorship is worthy of someone who is director of the Asian Studies Center at the University of Oxford, and whether this is a “SENSIBLE, RELIABLE, AUTHORATITIVE” account that Newsweek proudly proclaims on its masthead.

Iftikhar Dadi

Associate Professor

Department of History of Art

Cornell University

Mr. Iftikhar Dadi,

Your comment smells of shallowness and it is so disheartening for a person of your stature to stoop to such levels of pettiness. You should welcome any critique rather than start beating the bush. Everyone finds the article of Mr. Devji as an eye opener as to how Pakistani art / artists fate is dependent upon these few kingmakers, irrespective of the quality of work they produce !

Your comment clearly reflects the defence of these so called art gatekeepers as if you are a puppet / spokesperson of them. My respect for you as an Art Historian has totally diminished as you mention in your biased comment :

“I have never claimed that Imran Qureshi is “father” of the new miniature. I do note that he has “played a key role in training the next generation of miniature artists at the National College of Art” (p. 220), a role that Sikander never ever assumed.

Mr. Dadi ! What about Prof. Bashir Ahmed under whose tutelage, all miniaturist have emerged ! How can you say Ms. Shazia has not played any role ? Is it about just training or putting miniature art on world scene !

Harris A. Ahmed,

To Editors of NEWSWEEK re article ‘Little Dictators’

From Dr.Virginia Whiles

Faisal Devji’s article reads like a rant from a frustrated groupie. Shahzia Sikander will shiver with shame if she reads it. This is a foul text full of anger and subjective spite, for what reason? Clearly Devji has not read my book. I refer to Sikander on eight pages, citing her serious and humorous reflections on her Ustads at NCA and on the nature of the training in the practice of miniature painting. Her comments reflect her political awareness of the threats of patriarchy that dominate Pakistan, the kind of which is perpetrated in this article, and illustrate Devji’s total misreading of the feminist perspective in my book.

I know Shahzia Sikander and respect her work, the fact that she is not a protagonist in my book is because it is an ethnographic study of the specific practitioners of miniature painting whom I observed whilst participating as both student and lecturer in the NCA (National College of Art) from 1999 to 2002. Sikander had already left Pakistan when I arrived but her aura hovered maternally over the students, indeed she was a role model for the female practitioners. Devji’s ignorance of the context is proven by his erasure of facts: that Sikander and Imran Qureshi were co-students and united in their profound respect for Zahoor ul Akhlaq, and if anybody has to play the ‘father’ role to contemporary miniature practice, it is he, loved and missed by all of us who had the privilege of knowing him. (Sadly Zahoor cannot read Devji’s text as he would challenge him to fisticuffs and give us all a patriarchal laugh).

In response to his accusation of ‘re-writing art history’: where lies the ‘original’ art history of Pakistan? Devji’s implication that ‘artist-critics’ are an unusual product of Pakistan not only demonstrates his utter ignorance of cultural history throughout the world, it is an insult to the the honourable profession of criticism and the vital necessity of sustaining “a perpetual conflict of interests.” As Said wrote: “Criticism must think of itself as life enhancing and constitutively opposed to every form of tyranny, domination and abuse…”

As to his vitriolic accusations of ‘historical vandalism’, of ‘censorship’ and of ‘miming real world violence through acts of erasure’… and to crown it all ‘Little Dictators’, I will simply ask how an apparently eminent historian can cast such brutal stones on fellow comrades in search of speaking truth to power? There lies the anthropological, or psychoanalytical question.

Dr.Virginia Whiles

This article and the comments in response to it make for a fascinating debate regarding history and its alleged erasure.

May one suggest, as a non-scholarly yet modestly informed reader of Pakistan’s history and that of its art, that the truth is, as usual, somewhere in between? That is to say, neither are the country’s current critics and cultural csars blameless in their alleged excising of significant artists from the ‘canon’, nor are they deserving of such a harsh critique themselves as the moniker ‘little dictators’ Dr. Devji reserves for them.

There is precious little by way of art history, even of the textbook variety, existing with regard to Pakistan’s art. (Akbar Naqvi’s ‘Image and Identity: 50 Years of Pakistani Art’, deserves special mention here as a rambling, lovable, eccentric and rather poetic work) of Anything any scholars throw the way of us little people would be eagerly received – censorial or otherwise.

Dear Dr. Devji,

Thank you for exposing two of the caporegimes of Pakistan’s small yet powerful Art Mafia, in your recent essay in Newsweek Pakistan.

The purpose of my comment is to mention another instance of artist exclusion and to highlight the recently “self-appointed“ role of artist-curator in Pakistan which seems to be the next mortarboard to be worn by artists after the artist-critic role. (No reference to Quddus Mirza, of course & kudos to him for his current silence in the comments section !)

For the record, I would like to include a open letter which was written to Nazia Khan, the artist-curator of one of the biggest exhibitions in Karachi in recent years, “ The Rising Tide “ which also marginalized Unver Shafi & Amin Gulgee from the 42 artists in the show. Yet another example of manipulating the course of Pakistan’s art history and erasing important figures from it.

Best Regards,

Ardy Cowasjee.

Owner of Ziggurat Gallery, Karachi (1990-94)

P.S. Art needs an artist-critic like a fish needs a bicycle.

OPEN LETTER TO THE CURATOR OF THE RISING TIDE : NEW DIRECTIONS IN ART FROM PAKISTAN 1990- 2010.

8th Nov.2010

Dear Naiza. How are you?

I went to see the “Rising Tide “yesterday afternoon. The first thing that struck me when I walked in was the glaring omission of Unver Shafi and Amin Gulgee’s work from the exhibition that covers a period from 1990 – 2010.

Let me take you back to the early 90’s. These two artists had already gained more prominence in Pakistan by 1991-93 than practically anyone in the Rising Tide. They had solo shows nationwide and were written about by everyone. They were breaking new ground/direction in their field, in a country which had a dismal art scene at the time, where painting pigeons and carving wooden figures was the order of the day. This was at a time when a large percentage of the Rising Tide’s participants were having their fledgling group shows or hadn’t even finished art school.

I was someone who was promoting new directions in art in the 1990’s with the Ziggurat Gallery as you well know, and having shown Unver and Amin, I am curious to know on what grounds or valid criteria they were not included in the Rising Tide. Surely personal differences and other influences have to be put aside when dealing with a historical exhibition which appears to be undefined within any theme or one particular sphere of art, be it contemporary or cutting edge, painting, sculpture etc. etc. and envelops all the different facets of art.

I know it’s not easy to encompass 20 years of art in one show and people are bound to be excluded. But if I have to ask someone who artists as obscure as Polack & Hutcheson are (I called David Alesworth during the show), surely 2 of the most prominent Pakistani artists of the last two decades should have been included instead/as well !! Sadly all the reviews the Rising Tide has got, have failed to raise this question as well.

Perhaps this perpetuates my belief that artists should be artists and curation left to gallery owners and professional curators. But then as you know anything flies in Pakistan where the definitions of artist, critic and curator all blur their dividing lines!

I await your reply,

Regards, Ardy.

P.S. 13th Nov.10

Naiza replied 3 days ago. Unfortunately her reply was too personal and patronizing to print here. It was written in a fit of pique and it would lower the tone of this letter and will not reflect well upon her. Her main defence to their exclusion was as expected, that Unver & Amin’s work did not fit into the “theme” of the Rising Tide. A theme, that if it exists beyond being described on a board in the show, is one that is widely open to interpretation, and one she claims I failed to grasp !!

As a life-long student of art and development, with a focus on South Asia and interest in Pakistan, the Devji article resonated with me and brought into focus the current threats to promoting democratic ideals in art and culture.

I applaud Dr. Devji for recognizing and courageously highlighting an important topic for public discussion: censorship in the construction of a canon for Pakistani art, a construction that has clearly ignored a number of important artists. The bottom line of Devji’s article compels us towards reflection and improved collaboration for action and learning. After all, we have a shared responsibility in recognizing and exposing existing mafia-like operations of a small network of self-appointed gatekeepers and powerbrokers and demanding more transparent scholarship and greater accountability in the practices that govern a landscape of “Pakistani” art. The exclusionary behavior of a small network of individuals creates a zero sum game – a game that has very real and unjust consequences for many emerging and even some pioneering Pakistani artists. It also undermines historical integrity in the creation and dissemination of knowledge capable of promoting a just and inclusive narrative and meaningful dialogue and collaboration that embraces diversity in a growing community of practice among “Pakistani” artists.

The “smoke and mirrors” comments posted by both Dadi and Whiles in response to Devji’s article are disappointing. Alongside Quddus Mirza’s false propaganda, the two books in question represent a new way of writing histories of non-western modern art. Given the books have been put forth as inaugurating a “new field of critical study in relation to the modern and contemporary art of Pakistan” (Saloni Mathur, Art in America, 2011), we need to question the “cleansing” of important historical content (such as Shahzia Sikander’s pioneering contributions to the revival of miniature in the 90s), which represents a major limitation as it is clearly relevant to the new narrative and discourse that is being promoted. This limitation has absolutely nothing to do with the publicity of an artist but rather the merit of the content of her contributions and insights from her experiences that are relevant to the historical narrative of miniature painting and its revival as a credible, viable mode of contemporary expression in multiple contexts (global, local).

A Playbook of Exclusionary Tactics

Based on my review of a comprehensive bibliography of contemporary miniature and my knowledge of the current art scene in Pakistan, the tactics Devji highlights in his article are evident in the playbook of a well-orchestrated network of art wallas (the celebrated leadership and authorities associated with the art of Pakistan), who are determined to maintain their power and control. These tactics, taken together or triangulated into a whole, jeopardize the development of more inclusive processes that enable expansion of the field, the diffusion of power to many “centers”, and greater cross-fertilization of ideas and collaboration that ultimately benefit the field. The three tactics that contribute to systematic erasure include the following and are described in greater detail below: 1.) Frame and define issue characteristics for modern art in the South Asian context while dismissing important actors, not only with association to Pakistan but also to India and Bangladesh (Iftikhar Dadi); 2.) Re-construct a context selectively, re-defining important causal links between actors and associations over time (Virginia Whiles); and 3.) Create deliberate divisions through pronouncements questioning the legitimacy and quality of work of artists in relation to a self-defined community of practice and its self-determined standards of quality (Quddus Mirza and Imran Qureshi).

Tactic #1 (Iftikhar Dadi): Frame and define issue characteristics for modern art in the South Asian context while dismissing important actors, not only with association to Pakistan but also to India and Bangladesh

If Dadi’s study takes on the “intellectual history of the emergence of modernism in the

art of Pakistan and South Asia during the 20th century” and addresses “the challenge of terminologies and meanings for the study of modern art in much of the world”, then it remains incomplete without the inclusion of Sikander’s role and contributions as a key artist associated with Pakistan, with mature experience operating within the global arena. Despite Dadi’s response, this omission remains intellectually and experientially unjustified. It poses a significant limitation, given the widespread audience to whom Dadi hopes to “exemplify the richness of intellectual and discursive legacies of important regions of non-Western modes of artistic practice”. Dadi’s audience includes “scholars of modernism who remain narrow in their scope and clearly need to understand it in a genuinely global context, researchers in South Asia area studies who ought to incorporate cultural and artists developments much more in their analysis, students of Islamic Art who are perplexed when dealing with its encounter with modernity, and young artists from South Asia who do not understand their own history very well.” (Iftikhar Dadi, interview in Rorotoko, 2012).

I remain puzzled by Dadi’s omission of Sikander on three major counts:

• Methodological criteria and associated strengths and limitations of prioritizing a select number of key artists for a deeper exploration: While some general points associated with key artists included in Dadi’s study are mentioned in the introduction (“All the artists studied here have sought to situate their practice in the broader intellectual and social contexts of their eras and have also devoted considerable effort to building new institutional frameworks of exhibition, patronage, and reception for modern art”), the methodological criteria Dadi used to select or prioritize what he refers to as “key artists” (e.g. the ones from the 80s/90s that exemplify modern contemporary practice; focus primarily on “Pakistani” artists, etc.) and its associated strengths and limitations for topic of the book are not put forward in a transparent manner in the introduction. It is interesting to note that in the epilogue focusing on emergent practices, a total of 19 individuals (artists/curators) (approximately 10 of whom are artists in relation to contemporary miniature) are highlighted for their valuable contributions to advancing innovative practice and discourse relevant to the contemporary globalized art world. Even in the detailed endnotes, which provide explanations and websites for artists, galleries, curatorial projects, etc., Sikander is nowhere to be found as an explicit actor or a source of information worthy of mention.

• Framing modernism within a transnational context: Dadi’s study aims to rethink modernism through a deeper, context specific analysis of artists, including issues such as the complex engagement between tradition and modernity. Dadi states “the artists in my study ‘decolonized’ Islamic art via their artistic practice, by selectively reworking threads and fragments of classical Islamic art into modern formulations.” He adds that “modern art in the region of South and West Asia and Africa therefore emerges via a complex negotiation with ‘tradition’ with a resonant and affirmative encounter with transnational modernism . . .” Given Dadi’s interest in re-framing issues, such as modernity and tradition as binary forces and in opposition, Sikander’s contribution cannot be dismissed. Sikander’s track record of contributing to the modernist/postmodernist discourse within the global arena, which turned the simple tradition/modern binary on its head, spans at least a decade more when compared to the experience of the 7 artists who are featured in association with contemporary miniature in the epilogue. If Dadi is interested in pushing the envelope around modernism as a global aesthetic in South Asia, then Sikander’s experience as a transnational artist tackling and transcending the issues of interest, in association with scholars such as Homi Bhabha and Arjun Appadurai, would have added significant value to the efforts to re-frame them in this study.

• Evoking the second revival of miniature painting and drawing parallels with one of the key artists (Chughtai): Dadi’s interest in contemporary miniature is evident in the following statement: “the playfully subversive miniature today is better suited to participated in a global and postmodern culture . . .” (Dadi, ISIM Review, 2006). It is no surprise that contemporary miniature and associated artists feature well in the epilogue of Dadi’s book – particularly to extend the thread of engaging tradition. He mentions Akhlaq’s critical role and then generally states, “by mid 1990s, students began fracturing the traditional narrative and space of the miniature . . . .” He then continues to discuss the contribution of several contemporary miniature artists and concludes that Chughtai and the contemporary miniaturists have contributed to “a new type of postnational muslim aesthetic” (which could be contested as Whiles states in her review of Dadi’s book, 2010). In contrast, another individual who has recently published an article focusing on the contemporary miniature movement in Pakistan singles out Sikander’s role and significance in constructing this art-historical narrative: “The contemporary twist to miniature painting was initiated in the 1970s by the artist and educator Zahoor ul Akhlaq . . . he proposed a new aesthetic in miniature painting that involved blending the traditional art with the western and postmodern materials and innovations . . . .but it was not until 1992 that the current trend in contemporary miniature art really took off. One of NCA’s miniature art students, Shahzia Sikander, produced a thesis work that combined elements of miniature with a contemporary theme. Not only did her work have a personal narrative, its scale (at five feet long) was an outright contradiction of the miniature tradition. Since then, many students at the NCA have followed in Sikander’s footsteps with works addressing a wide range of contemporary subjects and themes . . . .” (Durriya Dohadwala, Reviving Tradition – Pakistan’s Contemporary Miniature Art, 2013). As a serious scholar who references the contemporary miniature movement and its revival as a continued interrogation of tradition, Dadi cannot do so with any degree of credibility if he equates Sikander with other NCA students in the 90s and chooses not to include both the context and content of her artistic innovations. Virginia Whiles criticized Dadi for not including Zahoor ul Akhlaq’s work in his book, as it would have balanced Dadi’s narrative as a missing link (Whiles, Art Monthly 2010). However, she was and remains silent on Sikander as another missing link.

Tactic #2 (Virginia Whiles): Re-construct a context selectively, redefining important causal links between actors and associations over time

Context – including all relevant milestones and enabling factors – matters for understanding the evolution and impact of any movement. Whiles uses an ethnographic approach to understanding the predicament associated with the revival of a traditional art form – miniature painting – and by association the basic conflict between tradition and modernity. The book’s limitations arise because while an attempt is made to contextualize the trajectory of resurgence in contemporary miniature (e.g. a full chapter devoted to the social, political and historical formations relating to miniature practice), the discussion of key actors and factors that enabled this movement to interface with the global arena remains inadequate. Whiles’ lack of substantive focus on a female pioneer (Sikander) serves to de-link important associations within this movement and give due visibility to her critical role as a bridge between the two groups/generations of interest in her study (the traditionalists and the iconoclasts/game-changers), ultimately diminishing her power as an actor and the influence of her original ideas to the current practice. Sikander’s innovations and influence make her integral to any discourse around the “imaginary of Group X (who experiment formally and conceptually)” and broader issues which the book tackles through Group X’s practice, such as: tradition and modernity; the miniature as a vehicle for social commentary; use of subversion and irony; and, the effect of globalization in miniature practice. In this regard, Whiles draws no substantial connections between Sikander’s work and that of the “new generation”. While mentioning the increasingly cosmopolitan nature of the miniature’s reception and “growing wings” in the last five years, she never bothers to trace back to who and what enabled this phenomenon. It is disappointing that despite over 7 years of research (including two years of field work in Lahore which inform the focus within this book) and a doctoral thesis focusing on maneuver in miniature, Whiles only gives perfunctory references to Sikander’s breakthrough innovations in her book, a book which is described as “a comprehensive account of miniature in its present role of defying tradition, setting new boundaries both in the art world and in the art market. . . “ (ART NOW) and “ . . . .the first in-depth look at this contemporary art movement which provides fascinating insight into the links between art and politics, and between indigenous and global aesthetics.” (Amazon).

Tactic #3 (Quddus Mirza and Imran Qureshi): Create deliberate divisions through pronouncements questioning the legitimacy and quality of work of artists in relation to a self-defined community of practice and its self-determined standards of quality

Public pronouncements or portrayals of issues matter – particularly when they constitute a misuse of power by actors who are intimately connected to the issues of interest. This tactic is evident in what appears to be a clearly orchestrated interview Quddus Mirza conducted with Imran Qureshi (ART NOW, December 2011). Their remarks are derogatory towards a peer who is integral to their community of practice and serve to propagate fiction that interfaces with the exclusionary tactics mentioned above to raise questions about Sikander’s image and contribution as an artist.

Perhaps there may be a way forward to remedy this absurd comedy of omissions and exclusions in the nascent historical scholarship focusing on modernism and the contemporary miniature movement in relation to Pakistani artists. Perhaps Iftikhar Dadi and Virginia Whiles would be willing to collaborate and accept my challenge to write a part 2 to their initial books, locating Sikander, and other key artists excluded, firmly within an attempt to continue their contributions to documenting the work of artists through a “deeper engagement with their specific trajectories” as a way to address the “challenge for scholarly understanding of much modern and contemporary global art in which historical and intellectual context remains largely unexplored.”(Dadi, Rorotoko interview, 2012). The brief epilogue on contemporary practice begs expansion into another book.

I like the article very much. As in all walks of life in Pakistan the harbingers of nationalism have rewritten many other histories, thus why should art be excluded. As has been my experience all histories of Pakistan are always rewritten to exclude the real heroes. Its a blight on that nation.